As the fields of various firearms technologies evolved, we’ve seen the capabilities of the different types of small arms grow in scope and diversity. What was originally the same gun shooting shot or ball, with a shortened pistol variant for belt carry, has become a wide variety of guns tailored to specific needs, with one of them being long range shooting. Today’s rifles can shoot a long way, but there’s no point in doing so unless you can do it accurately. In today’s article, I’ll go through an introduction to small arms ballistics, and what you can do to hit the target with each shot.

Physics, the bullet, and you

A bullet’s path is not like a laser; it doesn’t go in a straight line, and you’re not going to get the bullet’s point of impact to match where your sights are pointing at more than one distance (sometimes two) at a time. You’ve got to worry about a few different things while shooting at range, but the most important ones are elevation, windage, and range.

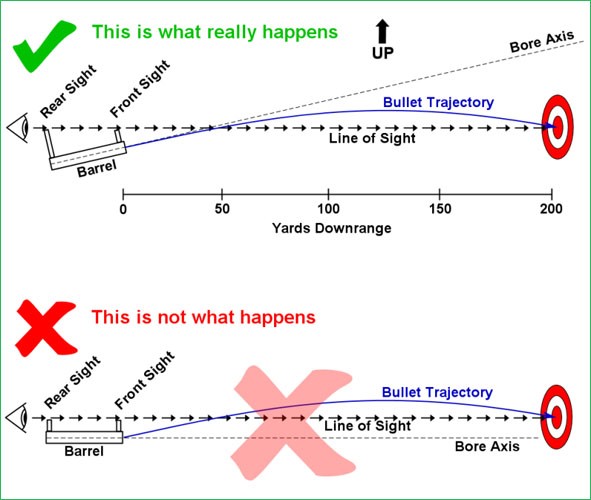

Elevation is fairly straightforward once it’s understood. Think of three balls. You drop one, throw one on a purely horizontal line drive, and shoot one out of a tennis ball cannon horizontally as well. Assuming they are all dropped from the same height, what happens? Those of you who paid attention in physics class will recall that they will hit the ground at exactly the same time. Put more simply, a bullet falls just like anything else.

“Ok, Luke, I understand; so a bullet will be two inches low at 200 yards, 4 inches at 300 and 6 inches at 400 and so on?” Not quite; there’s two problems with that. The first is, just like jumping off a cliff into a lake, you are accelerating downwards under gravity, so the longer a bullet flies, the faster it will drop just by gravity alone. The second is air resistance; the bullet slows down due to drag, and, as such, has more time to fall per horizontal distance traveled.

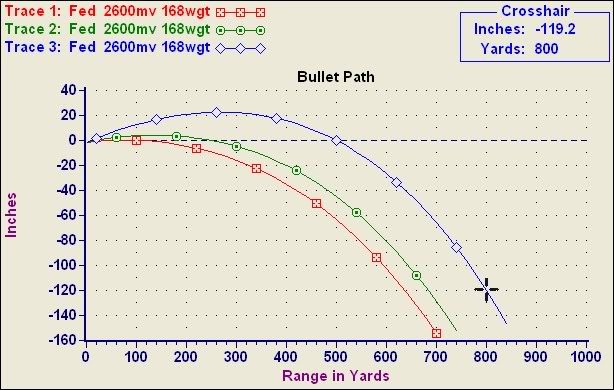

Note how the bullet is dropping faster (y-axis) as it gets further away in range (x-axis)

The takeaway on elevation is that, due to gravity and air resistance, bullet drop is fairly trivial at close ranges of a couple hundred yards, starts to play a big role at medium ranges of several hundred yards, and is monumental outside of 1000. Your typical, over the shelf rifle running a 5.56 or a .308 will run out of effective range quickly after 500 yards, be totally spent at 1000, and it is absolutely possible to miss spectacularly at those latter distances due to improper sight dope (data on previous engagements, i.e. “what does my gun do at this distance?”)

Windage is the effect of the wind on your bullet. Put simply, wind will blow your bullet off course in its direction. We have a few things to consider. Wind is considered full value if it is blowing 90 degrees to your shooting, as in, coming across the range, and half value if it is at a 45. If it’s blowing straight on, either from the front or the back, it matters less, and is fairly inconsequential at closer ranges.

Wind does silly things, and there may in fact be wind blowing from the opposite direction at your target than it is at the firing line. Wind tends to have more effect downrange, as the bullet is slower then than at close range, but the best rule of thumb is that less wind is better, and the less sideways it is is better, too.

Lastly is range itself. You must know how far you are away from the target in order to add the correct elevation to get the bullet there. On an actual gun range, the targets will be at set common ranges like 200 yards. Most rifles are set up so that they fire well at close range with the sights set to a default position. This is a concept called “Battle Sight Zero” (BSZ) and it means that you don’t have to worry about sight adjustments inside a certain amount of range. For instance, the M4 carbine has a BSZ of 300 yards; anything inside that range can just be aimed at and shot, you will be close enough. Outside of that, start dialing in elevation.

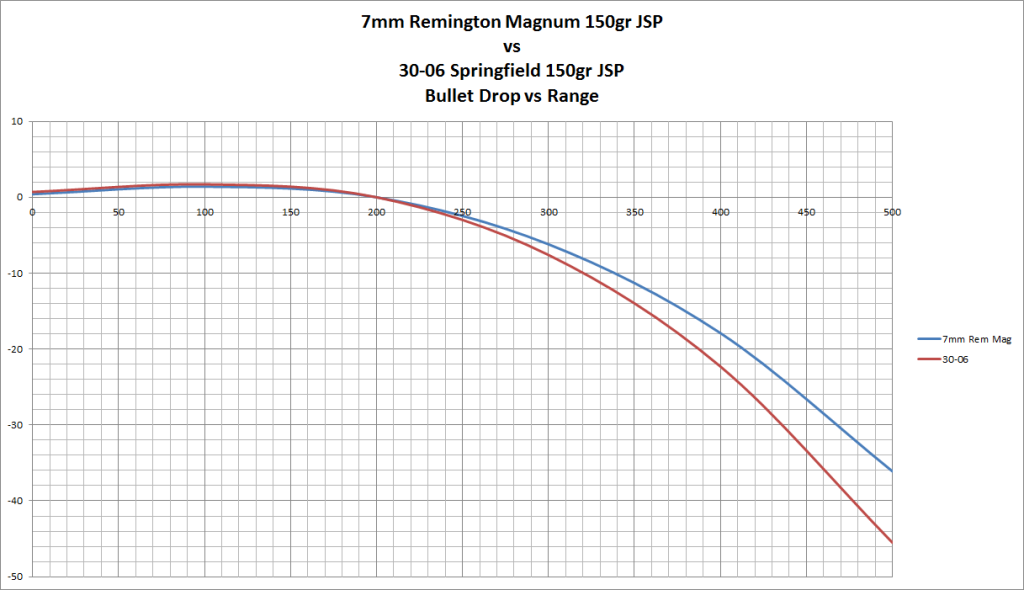

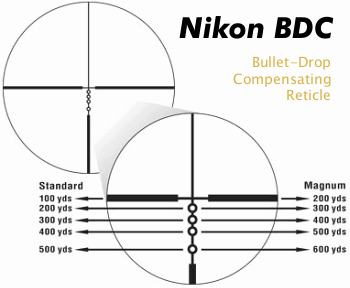

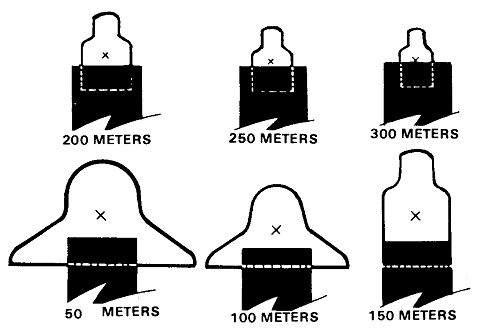

Bullet Drop Compensators are relatively new, you just use the appropriate bubble for the range and it takes care of the rest. You can see how close 100, 200, and 300 are, and that’s the idea of Battle Sight Zero; at closer ranges, you’ll still make effective hits even if it drops some.

The concept of “zero”

Many people go to the range, sight in their guns, and call them “zeroed.” Like said in a previous article, that’s not zeroed, that’s simply sighted in. There’s a difference between fixed sights (where the sights are soldered or dovetailed or simply part of the gun itself), adjustable sights (where you can set them for whatever single distance you want), and zeroable sights (where you not only make the sights on at a single distance, but you set the sighting system up to read correctly at that distance and others.)

Let’s use a couple examples here that are fairly straightforward to get the concept down. The first example is the US Rifle Cal. 30 M1, the Garand, and its sights. Garand sights are some of the best out there, and using them to explain zeroing works, mainly because they have both elevation and windage zero, unlike the M16 system.

Mechanical Zero. The right dial has the sight centered on the windage indicator at the bottom, and the left dial is backed down from the 200 yard “2” and the 100 yard (line below the 2) down to bottomed out at “12” (which is the max height, 1200 yards, once rotated around one full turn.

The first thing you do is set mechanical zero, which is when the sights are indicating on their dials that they are set with no windage, and no elevation. That means crank the windage knob to be center, and the elevation knob to be bottomed out. Garands happen to be set up for about seven clicks up off mechanical zero elevation to be close to being right, so doing that, then shooting at a 25 yard target is the first thing.

Garand Front Sights. Loosen that Allen bolt, then slide it opposite the way you want the bullet to go, just a bit, tighten down, and check again.

The second thing you do is leave the windage knob alone, and, instead, adjust the left/right to get on the bull with the front dovetail alone. See a previous article for sighting in. The rifle is now shooting straight left and right, and, just as importantly, it indicates no windage added, which means it is now zeroed for windage. If there WERE wind, and you were shooting at a range it would matter, you could dial in windage to shoot, then take it back out later, and be “on” again. That’s the point.

For elevation, you would actually use the elevation knob, but you don’t yet care what it says. Get it on the bull at 25 yards, then go to 100 yards and adjust as needed. Once on the bull there, you loosen the screw on the elevation dial, then twist the dial (which moves only the dial) to show “1” at 100, then tighten it down again. Now that you have done this, it is zeroed for elevation at 100 yards, and, if you wanted to shoot 400, you would crank the dial to “4,” shoot, then later reset to 100 yards at “1” and be back where you started. One should always leave sights set for close range work as a habit, you might not have time to change them.

Screwdriver on the screw you loosen to just move the elevation dial (which currently indicates 1 for 100 yards. (There’s only numbers on 2 and 4, 1 and 3 are implied with the lines)

For scopes with turrets (scopes with dials are simply adjustable and have no zeroes), the idea is even easier. You simply get the rifle shooting the way you want it, at the range you want it (which is usually a 50 yard or 100 yard zero), then you loosen the set screws which allow the dials to free spin, set them both to “0” (hence the name of the endeavor) and then retighten. You are now zeroed at that range.

Leupold M1 Turrets (I like these). This scope has zero elevation dialed in, and 1/2 MOA windage to the left. See the allen socket next to 13 on the right dial, that’s what you loosen to set the dials to zero once the rifle is shooting right at your desired zero’s range.

Shooting at range

Shooting at range has two additional steps than shooting at close up distances, but, provided you do your homework, it’s actually not any harder than shooting close. Those two steps are range estimation and sight adjustment, and they are followed by shooting as normally done.

Range estimation is vital. People cheat nowadays using range finders that bounce an infrared beam onto your target and measure the time of return to get the distance, but the old fashioned way is to know your sight’s architecture in terms of Minutes of Angle or Mils, and knowing about how big something is in real life, and comparing the two.

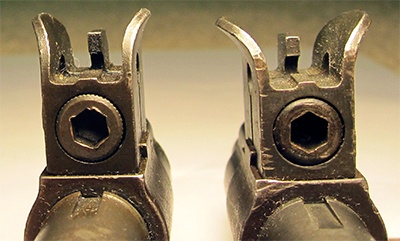

For an example, front sights on military guns are often about 4 minutes of angle wide. This means something 4 inches wide at 100 yards would be the same width in your target view, and so would something 8 inches at 200, 12 at 300, 16 at 400, and so on. A person, who is usually 20 inches wide, would be just as wide as your front sight on this rifle at 500 yards, and that’s also about the limit of iron sights.

Not the best graphic, but you can see how the sight width in relation to the target width’s ratio changes with distance.

More importantly, someone who is a little more than double the width of your front sight is a little under half the distance to 500 yards, i.e., 200, and you know where to set your sights, even though if he’s only 200 yards away, just aim at him and fire already, but you get the point; you use the ratios of the apparent size of your target to something you know about your rifle (either the sight width like we discussed, or the size of your field of view at a given power in your scope’s vision), and, by knowing how big it actually is, you can extrapolate the range.

Once you know the range, you either set it on the dial of your weapon that is set up for what you are doing, like iron sights usually are, or you add the appropriate amount of clicks to manually put in the MOA or mils of the “come up” you want. Let’s use the .308 Winchester for an example; it typically drops 4 inches at 200 yards, 12 inches at 300 yards, 28 inches at 400 yards, and 50 inches at 500.

Follow the red line from a 100 yard zero, to 4 inches low at 200 (2 MOA), to 12 inches low at 300 (2, 2 = 4 MOA), to 28 inches low at 400 (2, 2, 3 = 7 MOA) to 50 inches low at 500 (2, 2, 3, 3, = 10 MOA). Minutes of Angle (MOA) is roughly equal to your inches off center divided by your hundreds of yards range, i.e. 50 inches / 5 hundred yards = 10 MOA.

That’s hard to remember, but, if you put it in MOA, it’s easier, and becomes 2, 2, 3, 3. Remember, MOA is close to inches divided by the hundreds of yards, so a 4 inch drop at 200 is 2 MOA, and a 50 inch drop at 500 is 10 MOA, and that is the first and last ones of that 2, 2, 3, 3 thing (2 and 10). This is simply a rough guide, you will develop specific come-ups for your own rifle, and should write them down and have them handy when you go shooting.

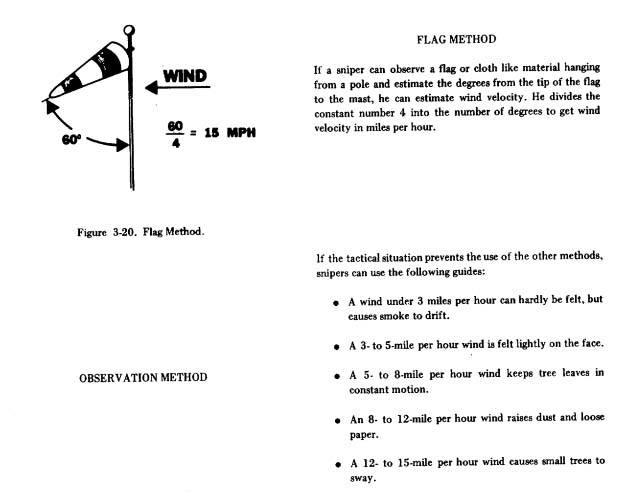

For windage, if it’s a near constant wind, you can figure out how fast it is going by an anemometer (wind gauge) or you can observe the effects from the wind on plant life and flags and extrapolate. You can then plug that into a chart for your bullet type, or you can use a Marine formula of the hundreds of yards you are shooting times the wind speed divided by a math constant of 15 for a close number, ie, a 300 yard shot with a 10 mph wind needs 2 MOA of correction.

This is rapidly getting beyond the scope of one Return of Kings article, so I’ll end on windage with, for most shooting, it’s enough to simply “hold into the wind” i.e., shoot towards the side of the target the wind is coming from and you’ll be fine. Elevation compensation, however, is serious business and you’ll end up in the dirt in front of the target if you don’t do it right.

Conclusion

Most anyone can be dangerous with a gun at close range, but it takes some actual skill and practice to be able to shoot at longer ranges. Whether it be for hunting, fun, or preparing for any sort of threat, a man ought to know how to be effective out to 500 yards. Be safe.

Read More: How To Properly Fire A Gun

“Just put your eye right up to the scope, aim and shoot. It’s not that hard…. That a girl.” https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/7aa6c1a4cd1ce69422a47b58d96b8ce7ebde1742268588ff961ee49227f30587.jpg

Ha. I’ve scoped myself before and had to have it superglued together at the ER. Still have a subtle scar above my eye.

Five bucks a round to shoot the DE but this ones worth every penny.

Last ditch side arm, too heavy to be practical. Good for stopping angry big game coming straight for you though.

If you were getting charged at, would be great to have. Otherwise it’s a novelty item. Just my opinion though. I’m not a gun expert. For $1,500 you could have 2-3 nice side arms. I have the baby eagle .40. It’s a nice gun. My next buy will be either a Springfield 9mm or a CZ 9mm.

Well if someone is hiding in a tree or the moon the recoil could be useful. Bloody swear the kick for me, a bolt action rifle would be smoother.

40 good. 45 bit over the top but can tolerate ( mostly the sound ). 9mm like a laser pointer.

90 percent of the time those guys who give little women big guns with no training and then sit back with a shit-eating grin also look and act like the biggest faggots you will ever meet.

Agreed but there’s no shortage of decent men who would happily show this girl how to shoot without acting like a fag.

Always wanted a 1911, and a couple of years ago Sig had a two-for-one deal, you bought the .45 pistol and got the .22 pistol for free. The .22 is full size, exactly same ergonomics as the .45 (although the .22s internal are a bit different). But it’s great for teaching newbies. Work up on the .22 learning the controls, I have them step up next to an FEG Hi-Power clone 9mm to deal with a little more recoil. Then the .45.

Always a good time and you tend to get them interested in continuing vice scaring them off it.

Sadly I’ve heard many a tale of guys who were hyped up on Dirty Harry doing much the same thing with “the most powerful handgun in the world”.

Or the ever classy crescent scar from sticking your face too close to the scope when firing.

First mistake: Firing in a bikini top. Might come back with some nasty burns.

No it’s cool, she’s one of the guys.

Had a 556 land right on the back of a guys neck. Made a perfect little brand of the casing on him.

Haha, he’ll have that forever.

Damn ! Glad the stupid bitch did not put a hole in her head !

That guy knew exactly what was going to happen. He couldn’t get far behind her fast enough.

Always be careful when a chick has a gun in her hand. When they hit the target, they get excited, jump and pan the range with the hammer cocked. Makes for a good adrenaline rush.

lol I know less than nothing about guns and even I would know to stay far away from a woman shorting one

Something like this? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bQU4mjE2pQA

See how you can put two and two together. To some, common sense, to others, genius and here we are.

Ok, I’m thinking you and I might be on the same level, or perhaps dimension. I’m a south paw and a little bit weird so I think I know where you’re going with this. Plus I just had a few beers.

I can’t even watch that, I’m just going to assume she had to have it surgically removed.

Pfft, I’ll just spray and pray.

BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRT!

Sounds good. You draw the fire and I will shoot heads off from cover.

If you want to learn this stuff really good, I highly recommend this channel. It has EVERYTHING. Everything you need to know, from start to end. You don’t have to be a pussy and be like “that’s a lot of videos I can’t be a cuck giving all my time to everybody else and have time to watch those videos!” or be like a millennial and go all like “OMG can’t they do that in one listicle I literally can’t even!”.

This is the stuff. I have been doing this stuff for YEARS and when I watched this series, I was looking back on a lot of wasted money for equipment purchased incorrectly. You cannot go wrong with this video series. You will learn internal and external ballistics, You will learn how to generate external ballistic tables. You will learn how to do a calc sheet. You will learn how to select the proper equipment for the range you want to engage at.

I shit you not.

When you are done reading this article, go to this channel

Yes sir this is a great site on you tube.. The only other thing I can recommend to learn the fundamentals with iron sights is to go to an “Apple seed” shoot. They are all over the United States, and the cost is very affordable. If you can shoot “rifleman”, you will be ahead of about 90% of the people out there who shoot a rifle, and more importantly you will have a good foundation for further growth adding in scopes and higher quality ammo and rifles. But this is a great place to start. Be able to hit a man size target out to 500 yards with a “rack grade” rifle, iron sights, ball ammo, and from field positions. Great article Luke!!

Suck with a scope. Suck with sight adjustment. Fixed open sights and basically dur if redundant aiming with barrel…I hit things. Works for me…sorta like using the same oven temperature, just adjusting cooking time.

Next article, how to make cool music with M1 Garand’s

You need to do your homework if you’re going to shoot like a pro, that’s for sure. Speaking of taking shots at things, yet another bowl game is now in the books. BYU just beat Wyoming, 24-21, in the San Diego County CU Poinsettia Bowl. Your old Uncle Bob had BYU to win, which gives me eight correct picks out of the nine games played (33 left to go), in ESPN’s Capital One Bowl Mania. This win vaulted me from the No. 475 position, to No. 321, on the leader board. I’m creeping up on the leaders like cheap underwear. Most of my biggest bullets have yet to be fired (in terms of confidence points assigned to games), and the leaders have already fired most of theirs (heh-heh). I’m only 32 points out of Position No. 50 right now. So watch out suckers, Uncle Bob is sneaking up behind you, poised to make a move like a freight train in the lane. (Click image to check out my score and position.)

https://uploads.disquscdn.com/images/2618928ec793e46b3c8b4ef515e92f06649af02a03fd93f223d9e2b7eccbe73d.jpg

I’ve bought that book in 2008. Don’t ask me to tell you it is the best reference, but I can tell you it helped me a lot to understand many basics about ballistics :

https://www.amazon.com/Understanding-Firearm-Ballistics-Robert-Rinker/dp/0964559854/ref=pd_sbs_14_t_0?_encoding=UTF8&psc=1&refRID=79NNVKG67DX89V2YXPVZ

Great article. Once yoiu make a committment, there is so much potential for learning new skills. First just learning to fire the dang thing. Second, dismantle and cleaning. Third, operationality of forearm. Things like sighting, adding new features etc.

I am sort of between 1 and 2. (And I understand it does not all have to necessarily be done in that order.)

I have a couple of decent shooting buddies. Especially a Ukranian dude more knwoedgeble than I am. But what I really would like would be someone to hang out withtaking apart and cleaning guns like I did in basic.

One of the few things I enjoyed most about the military was sitting around with the dudes, cleaning guns and talking shit. But at 52, just not many people with the time or desire to take you up.

As a young dude, I did not enjoy my male friends enough. All I thought about was chasing pussy. As a married 52 year old, what I want more than anything is dude friends with similar hobbies and interests.

One big diffrence between dudes and women. The sisterhood makes likes of friends really easily. They can just get together as a group and be girlie-girl friends socially. I don’t get it completely, but my wife is that way.

Dudes need a common interest or project. A hobby, music, guns etc. That is one of the things that sucks the most about how the PC army is today. Women have to stick their fucking noses into every dudespace. And then, they complain that the dudespace does not suit them.

Very well put. I find myself in a common mindset…maybe it’s a quasi-old timer attitude (I’m 54 yrs old). I think about how important chasing tail was when I was younger and just shake my head…what a fool I was.

Before you spend the minimum $6,000 needed to shoot quick and consistently well past 1000m use a program called Shooter Ready. It will train you to do the math on ranging and adjusting your turrets for $30. There is a free demo.

Then there is a simulator called Arma3 with a “mod” called ACE3 where you can practice even more, with stealth stalking positioning comms and overwatch thrown in the mix. $60

It takes a steady hand for those long shots, once past about 150-200 yards everything starts getting really small. There’s a lot more room for missing than there is for hitting.

Timely article. I disagree with saying that bullet drop is not important at below 200 yards. Yesterday I had a terrible shot on a caribou from higher elevation and a longer distance than I am used to (150 yards vs the 100 of the gun range) and took out the poor girl’s legs. Luckily she couldn’t run so I was able to put her down quickly, but yeah, elevation is a thing to worry about.

…and once you’ve done all that, get a good spotter to help you. I’ve shot just about every kind of rifle known to man, at all kinds of targets, and I STILL don’t shoot at anything further than 300 yards without a decent spotter to “call” the shot and help me dope the wind.

And rule of thumb: spend as much on the scope as you spend on the rifle. Or more. A 20x Swarovski or Zeiss scope ($2,500) sitting atop a Savage 111 ($550) will yield sub-MOA results, but a $200 20x scope will make even a blueprinted Remington 40-X rifle spray bullets all over the place.

Also: your choice of ammo is critical. If you don’t reload (and if you’re serious about long-distance shooting, you almost have to), then find the ammo your rifle “likes” best, and buy as much as you can from the same batch #.

And if you’re REALLY interested in long-range shooting, go to Boomershoot and prepare to learn.

The M16A2 and A4 have adjustable windage and elevation dials.

With the 5.56, getting a rough zero at 10 yards should put you on target at 200 yards for more precise adjustments. That’s how we did it in the Marines.

Practice…..then practice some more. Once your are done with that, practice again. Shoot at targets so much your eyes bleed, then do it again, and again. There is no other substitute.

Practice correctly though. Lots of practice doing it wrong will make you really good at being bad.

True, I suppose that is with anything.

No adjustment for coriolis effect? Teasing…