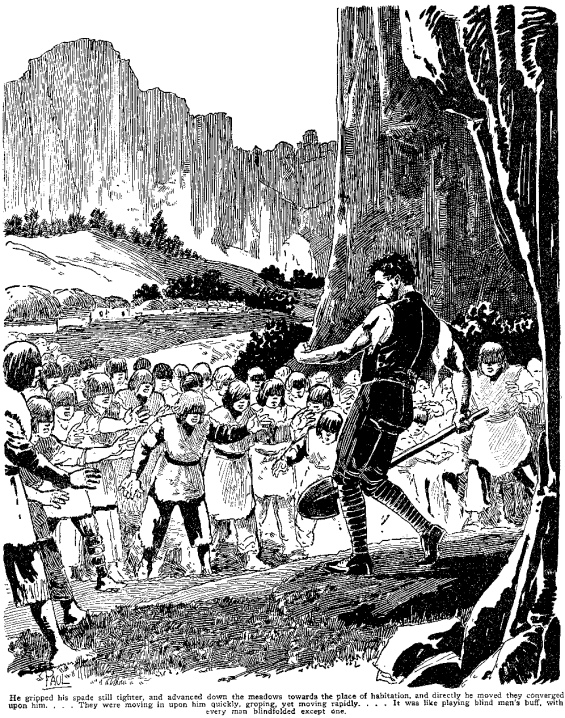

In H.G. Wells’s 1904 short story “The Country of the Blind”, an explorer in the remote Bolivian Andes discovers a long-isolated society of people who have become blind due to some congenital aberration, amplified by generations of inbreeding. The society has developed and been maintained with no concept of the sense of vision. He is taken in by the people and befriended by them. When he tries to explain to them the meaning of sight and the visual wonders of the world, they laugh at his delusions. All unanimously conclude that this wild-talking outsider is troubled at best, dangerous at worst. Falling in love with a local woman, his persistent efforts to explain vision to her gets him in trouble with the local elders, who conclude that he is suffering from a dangerous virus and should be forcibly blinded “for his own good.” Eventually getting wind of this plan, the explorer is forced to make a desperate escape through the mountains, nearly losing his life in the process.

This little parable is instructive on several levels, but for our purposes it serves as a sobering reminder of the power of groupthink and mass psychology in suppressing the individual. Those who parrot the party line, who genuflect before the altars of the officially-sanctioned idols, can expect to be rewarded with praise and crumbs from the table of the master. Those who question the idols—i.e., those who dispense “red pill” wisdom—can expect quite different treatment. And so it is with modern American society.

It has becoming increasingly clear that modern American culture will be characterized by political cowardice and paralysis and accelerating social decay for the foreseeable future. To fill the void of authority left by rotting social institutions and a near-vanished nuclear family, the government will become more and more authoritarian as it frantically strives to maintain public order. Increased surveillance, travel restrictions, exchange controls, and other forms of expanded state power will become accepted and routine.

Nothing can be done to arrest these trends. The decline is irreversible. At some point, if not already, America will be unable to offer its ambitious young men either a decent job or decent women. If a man cannot even have these basic, minimal requirements for his health and happiness, what does he really have? What conceivable reason, then, would he have to continue to grind out his life under a corrupt and degenerate system that denies his masculine identity, suppresses his ambitions, and relegates him to second-class status?

Exile, or some form of expatriate status, may become a rational alternative. We must have the courage to call things what they are, and to make decisions based on reality, rather than on what we wished the world to be. In this respect, the Europeans are well ahead of us Americans. To a far greater extent than us ignorant, arrogant, spoiled Americans, Europeans have lived through wars, revolutions, civil unrest, collapsing economies, famines, and pestilences. Historically, Europeans are far more inclined to pick up and move when necessary, to migrate when required: they have been doing it for centuries. To an American, exile—that is, leaving America for another country—is nearly unthinkable. But it may be time to think the unthinkable.

But how can one cope with exile? How does one handle the shock of leaving one’s country, and face the likelihood of a reduced living standard, the loss of reputation, and the feelings of isolation and loneliness? This is a question that I have turned over in my mind for a long time. I gained a fresh take on the issue from an unusual book that has recently been translated and published for the first time, after languishing, nearly forgotten, in undeserved obscurity for over five centuries.

Forgotten, that is, until now.

The Italian Renaissance humanist Francesco Filelfo (1389-1481) had personal experience with exile, having lived in an age when it was common for men to relocate when necessity called for it. He wrote his treatise On Exile as a consolatory exercise, to describe how a man could turn the experience of exile—with all its associated hardships—to his own advantage and even profit from it. Written in the form of a dialogue, it is packed with examples from history and philosophy to demonstrate how being forced to leave one’s country can even be a blessing in disguise. These are the main points I took away from his work:

1. Embrace the Renaissance concept of the “universal man.”

This is a whole new way of viewing the concept of manhood. You are not a citizen of a specific region or country. Reject narrow parochialism or nationalism. You need to see yourself as a citizen of the world, a universal man, whose happiness is not dependent on geographical location. The true “universal man” has attained wisdom by his study of virtue and philosophy.

2. Cream will rise to the top.

Wherever a wise man has decided to live, he will always live there either as “the first citizen or among the first”. You will find a way to earn a living and provide for yourself. Do not fear. The soul of the universal man is a “prime mover” in the sense that it moves itself, rather than being moved by outside forces. As such, his soul is indestructible and eternal.

3. Follow your heart.

You are happy to the extent that you know your inner self, follow your natural inclinations, and never depart from them. If you are forced to leave your country, know that it is not so much that you have rejected your country, but that your country has already abandoned you.

4. The soul of a great man will not submit to Fortune in such a way that he does anything base or low.

Rather, the power of Fortune, even if it brings bad things, should be seen as a training ground for the great man’s own virtue. No truly wise man has ever been harmed by exile.

5. Have a comprehensive philosophy of life that you can draw on to sustain you.

It doesn’t matter so much what it is, as long as it leads to virtue, you believe it, and it gives you the strength of a lion. If you don’t have one, get one. Fast.

6. Reject the treadmill-like pursuit of riches and fame.

It only leads to more unmanly craving, and leaves you unsatiated. For the study of virtue, examine Stoicism, Platonism, and Epicureanism.

For anyone who has wrestled with the thought of leaving America and the possible trauma it could bring, Filelfo’s book On Exile may be a comfort. He shows that the secret of coping lies within us: polishing our own souls, striving to be that “universal man”, and focusing on what we can control, not on what we cannot control. I am not saying that the time has come to hit the eject button. But we should all have options at our disposal. We should all have our escape plan. It is time to think the unthinkable.

Francesco Filelfo’s On Exile can be found on Amazon.

Read More: What Does It Feel Like To Be Betrayed By Your Own Country?