Nature has granted us extensive powers to observe, and to draw inferences from those observations. For most of us, observations are blithely made and discarded, in the hundreds upon hundreds every day. Even if we make a significant observation, only rarely do we have the presence of mind to ask follow-up questions; and rarer still do we have the conviction to draw the ultimate conclusions from what we perceive. What separates the average man from the truly exceptional man is this: first, the latter will instantly recognize an important observation when he encounters it, and second, he will have the courage to probe into the implications of this observation, regardless of where his conclusions will lead him.

But is there anything more rare than this type of man?

Far, far too often, we censor ourselves, and we hold ourselves back. We timidly suppress our boldest observations out of fear of social opprobrium or the mockery of the herd. But there is nothing more awe-inspiring than the example of a man who is able to see something of importance which no others have recognized, who has the intelligence to ponder the observation, and who then possesses the moral courage to make devastating deductions in the face of popular resistance.

It is the power of the will, displayed in all its muscular radiance.

So the great French philosopher Rene Descartes, lying sick in his bed and watching the movement of flies on his ceiling, began to make inquiries which would lead to the development of analytic geometry; so Albert Einstein, bicycling through the Viennese countryside, began to think about what it would be like to ride on a wave of light; so the great astronomer Christian Huygens measured the relative distances between stars by peering at them through small hones drilled in brass plates; and so the Greek scientist Eratosthenes was able to make perhaps the most sublime and beautiful observation in all of geographic history.

We will discuss him and his greatest achievement now.

Eratosthenes (c. 275-195 B.C.) was a driven and brilliant scholar whose erudition on many fields earned him the position of rector of the Alexandrian Library during the reign of Ptolemy III. His rivals and jealous colleagues liked to tease him with the nicknames pentathlos and beta, for his distinction in many fields, while always supposedly being second (beta) best. But as we will see, he was anything but “beta”. By the age of forty, his list of achievements was already astounding. He was a paragon of Hellenistic learning.

He wrote a history (Chronographia) of the major events of Mediterranean history, a volume of verse, and even a history of comedy. As a mathematician and scientist, he discovered a mechanical method for finding mean proportions in continued proportion between two straight lines. He measured the “obliquity of the ecliptic” (an astronomical term related to the orbit of the Earth) to an error of only one half of one percent.

But he was anything but a narrow-minded bookworm. Alexandria in his day was perhaps the world’s most cosmopolitan city. Greek in culture, but international in population, it possessed large numbers of foreigners from all over the Near East and the Mediterranean world. Traveling frequently and conversing with merchants, traders, and military men, he was able to make his Geographica the most authoritative treatise on geography for several generations. Unlike many men of his era, he was free from ethnocentric chauvinism, and believed men should be judged only on their actions, not their country of origin. Many Persians and Hindus, he counseled his pupils, were more honest and refined than Greeks, kept their word more frequently than Greeks, and had a greater aptitude for good government and social order.

But his greatest achievement, and one that will forever be a classic example of the power of deduction from the most rudimentary tools, was his measurement of the Earth’s circumference. Like many achievements of genius, it is unsurpassed in its simplicity and profundity. Let us examine just how Eratosthenes achieved this feat, more than a thousand years before the European discovery of the New World.

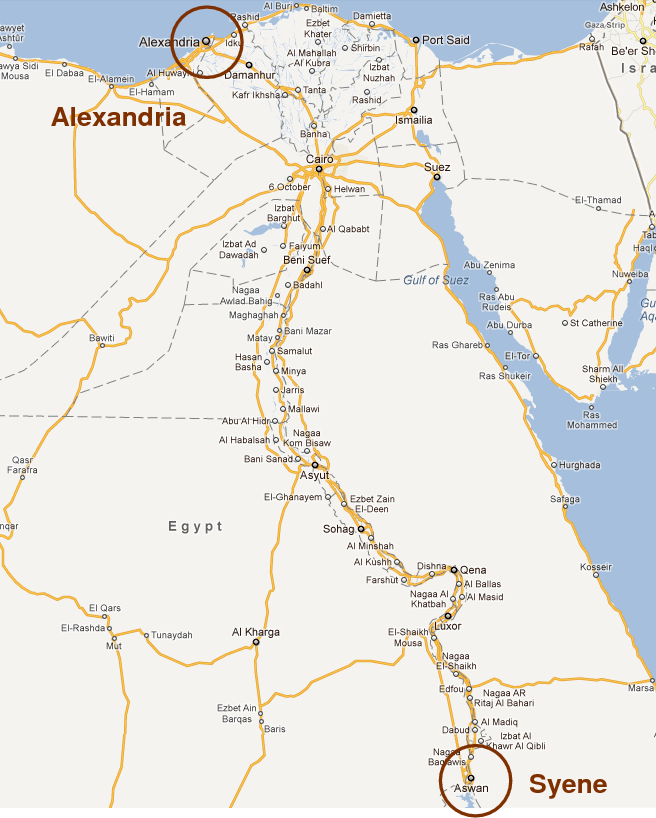

In Alexandria, he chanced to read in a book (or overheard a colleague mention) that at noon on the annual summer solstice (June 21) the sun at the city of Syene shone directly over a well. Residents of Syene were able to see the bottom of the well illuminated from the rays of sunlight shining directly overhead. The illustration below shows the details.

On June 21st of each year, the sun was directly overhead at Syene, but cast a shadow in Alexandria.

Now, this bit of information would have passed unnoticed through the ears or eyes of the average man. The solar illumination of the well in Syene had been going on for generations, and no one had ever given it the slightest thought. But Eratosthenes was not an ordinary man, and such men have the ability to take seemingly insignificant pieces of information and then use them to draw shattering conclusions. What he did next shows the analytic powers of the human mind at their very best.

Map showing the distance between Alexandria and Syene in Egypt.

He asked himself a key question: why are no wells in Alexandria illuminated by overhead suns on the date of the summer solstice? What explanation could there be for this phenomena? Eratosthenes knew of the sphericity of the earth; it had been taken for granted by his predecessors Aristarchus and Hipparchus, and perhaps the idea even went back to the Babylonian astronomers. But none of his predecessors had the patience or conviction to follow their observations in a systematic way. Eratosthenes did, and achieved immortality.

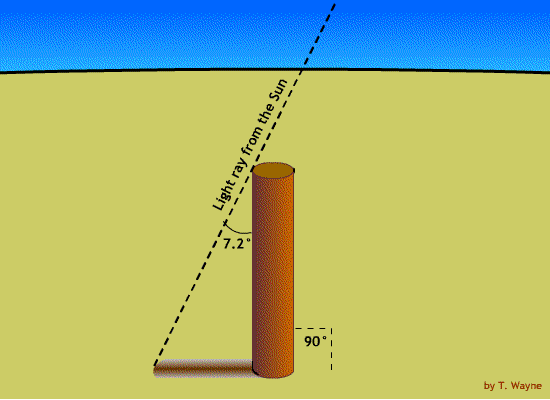

He noted that on June 21 in Alexandria, an obelisk cast a shadow on the ground of 7.5 degrees from its apex. He measured the distance between Alexandria and Syene, finding it to be about 500 miles. In the diagram below, the letter “s” represents the distance between Alexandria and Syene.

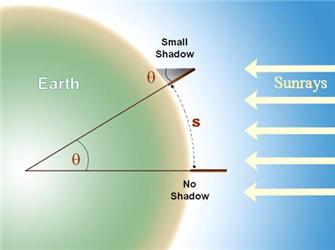

Diagram showing Eratosthenes’s experiment. The sun is so far away that its rays arrive parallel.

Putting this data together, he then sketched it out as a problem in geometry. The diagram below shows the well at Syene, the obelisk (or tower) at Alexandria, and the distance (represented by “s”) between the cities.

Since opposite interior angles are equal, the two angles represented by the letter theta are equal.

Now Eratosthenes knew from basic geometry that opposite interior angles are equal. Thus, if the angle of the tower’s shadow at Alexandria was 7.5 degrees, then the angle enclosing the arc of the circle from Alexandria to Syene must also be 7.5 degrees. The two angles represented by the Greek letter “theta”, in the diagram immediately above, are equal.

It followed from this that an arc of 7.5 degrees on the Earth’s circumference must equal 500 miles. And if 7.5 degrees equaled 500 miles, then, using simple logic, 360 degrees (a full circle) must correspond to about 24,000 miles.

This turns out to be very, very close to the correct answer. It was an amazing performance to draw such an immense conclusion from such a mundane observation. Observation: a well in another city is illuminated by the sun a certain day of the year. Conclusion: the circumference of the Earth is 24,000 miles. I love this story because it shows just how powerful a man’s will and conviction can be if it permits itself the freedom to soar.

It all seems so basic, so simple, in hindsight!

Except it isn’t. Great moments of inspiration always seem “easy” to achieve in hindsight. Especially when someone else has done the work. And such moments can come in very unexpected ways, as when Archimedes, immersing himself in water, discovered the principle underlying specific gravity. We all have such “eureka” moments, in one way or another. But who among us has the courage to act on them?

All of us have the power to observe. What we do with those observations is another matter. We can choose to ignore them, or to catalogue them away nicely, and refuse to act on the implications of our observations. If we have faith in ourselves, and if we have the courage of our convictions, we will approach the world with the fearless spirit of Eratosthenes. We live in a world where information is all around us: we can barely escape it. The problem of our era, and the challenge for us, is not so much finding information, but rather it is having the courage and conviction to act on what we know.

Act now. You already have made the observations. You already know the data, and you know the terrain. You are unlikely to know any more later than what you know now. Have faith in your own perception, and learn to trust your instinct. Take things one step further. One leap further, as Eratosthenes leaped. And an ocean of discovery, and perhaps even immortality, will await.

Read More: The Power Of Shame

Very nice Brother Quintus Curtius.

These kinds of inspiration give hope about life and are an important to balance all the bitterness from the gender war.

More please.

Thin-Skinned Masta-Beta

I’ll keep ’em coming.

BTW, I dig that weird name you got there, bro…”Thin-Skinned Masta Beta”….kkkkkk. Sounds like either an old Jackie Chan movie or the missing member of Wu-Tang.

My latest observation, that I’ve spent a good deal of time contemplating since my last voyage out of The Matrix, is that Americans live in a cocoon. American men and women alike want to – nay, INSIST on being insulated from reality by several layers of fantasy and wilful ignorance. Living inside a cocoon has become so ingrained in our culture that it’s everywhere you turn.

Howard Beale describes it best: “It’s like everything everywhere is going crazy, so we don’t go out anymore. We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller, and all we say is, ‘Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and my steel-belted radials and I won’t say anything. Just leave us alone!’”

God is the TV for most people. Mass media, endless shopping and acquisition, and recreational eating has become a poor substitute for a life well-lived in America. Not to mention men settling for wives that resemble barges and have probably had more cocks in one night than women used to have in a lifetime. They’d rather write a check to shut the bitch up rather than dumping her fat, pasty ass and finding a real woman.

How lucky are those of us who have the keen power of observation to draw conclusions and to abandon this cloistered lifestyle. Just realize, some people will fight you to the death to stay exactly where they are. Let them.

Plz make Relampago a contributor!

I suppose it’s all a matter of perspective. I work in third world countries regularly (thankfully, not as much as I used to); the real third world, not the entertainment districts but the places where commerce happens, and there are commonalities- a smell of human shit, rampant corruption, classism and proud willful ignorance among the underclass, and marginal intelligence among the rest. I guess my experience has been different than yours. I very much appreciate the US every time I return. Granted, I liked to have my fun with the local women, and learned to leave American women at arms’ length, but I think you’re oversimplifying and engaging in some popular tropes here that are a bit hyperbolic. Our materialism pales in comparison to that of most other cultures- we generally will not sacrifice food security for a Yankees baseball cap, or live for 2 months without electricity to pay for an iPhone, yet these are common practices elsewhere. I work on ships, and regularly interact with 3rd world nationals who can tell me the stats of my laptop just by looking at it, since they look at tech advertisements the same way we older guys used to look at the bras and ladies’ underwear section of the sears catalog when we were 12. We have massive wealth even among our poor, who live better than most of the world’s middle-class equivalent. Our news is politically-aligned, but you will find that Americans have a better nuanced view of realpolitik than most- Our geographical isolation and economic dominance has allowed a certain insulation, of course, but has also bred a larger proportion of critical thinkers. Though I love my foreign in-laws dearly, they’re vapid, superficial ignorant people who can’t adjust to planning further than 36 hours ahead in life, despite many advantages.

Anyhow, before i rant more, I enjoyed your last paragraph very much. Still, we may influence their thought processes, but we can not change or control other people. Just ourselves.

It’s all a matter of perspective.

Not having lived in Third World countries, I don’t have the firsthand experience that you do. But, having lived abroad myself and seeing the lower-class foreigners around me daily, I can extrapolate this to some degree.

The world’s poor, of course, want to improve their lot in life and they see commercialism as the most expedient way to do this. One, it increases their cred among their peers, and might even get them jobs to pull them out of the muck of their shitty lives. It also increases their cred in the eyes of the First Worlders that they hope to emulate and join one day. Trouble is, they fail to recognize that we First Worlders have our own problems. Still waiting in line for the latest iPhone, I suppose, is better than living in terror of the local warlords and their capricious actions.

Amen. Well said!

I don’t know specifically which countries you’re talking about, but I think Aldous Huxley said it best: “To travel is to discover that everyone is wrong about other countries.”

I’ve traveled extensively in Latin America and spent time in Asia and the Caribbean (not just the tourist areas) and haven’t come across the smell of human shit yet. Rampant corruption, classism, and wilful ignorance/marginal intelligence are something I can walk down the street and find right here in America. Hell, I can find all of that in the office I work in. Some of the most evil people I’ve ever met are those I have to work alongside every day. Here in America we are just able to more successfully put a smiley face on it and a divert everyone’s attention from our corruption, classism and ignorance/stupidity. Some of the stupidest, most closed-minded and duplicitous people I’ve ever met are home grown, right here in ‘Murica.

I actually get into a foul mood when I have to come back, because I know what I’m coming back to. Basically, I’m coming back to a Police State where the women rule every institution and problems that don’t exist are created just for the purpose of profiteering (the pretext for war in Syria being just one example of a system that can’t function any other way.)

I guess the main reason I enjoy being abroad is I feel freer than I have ever felt in the U.S. The only reason I do come back (for now) is because I’ve invested so much of my life into my career that I expect to get some sort of financial return out of the deal.

Well done. Very well done.

Great article QC.

You’re right, when something like this is spelled out, like you have in the article it becomes all too obvious. Just basic geometry. I think that is a problem with education today. There is no discovery. Students just seem to learn by rote what other men have already discovered. I wish there was a better way.

Another great observer was Darwin. I think his observations took a bit longer to crystalise into a theory than in the case of Eratosthenes. Also a lot more grunt work collecting samples. But in the end the Darwin’s theory is just as simple and elegant.

“There is no discovery. Students just seem to learn by rote what other men have already discovered.”

In the bulk of academic work, original thought is actually discouraged (“cites and references please”). Sure, when you simply need to explain ‘what is’ that is the approach, but if you stop there you will be forever limited to repeating what someone else already knows. “What could be” is just as, if not more, important than “what is”, or otherwise we would still be living in caves.

“There is no discovery. Students just seem to learn by rote what other men have already discovered.”

In the bulk of academic work, original thought is actually discouraged (“cites and references please”). Sure, when you simply need to explain ‘what is’ that is the approach, but if you stop there you will be forever limited to repeating what someone else already knows. “What could be” is just as, if not more, important than “what is”, or otherwise we would still be living in caves.

Since this blog discusses differences between men and women, how about this observation from my little world:

Is That What Love is? The Hostile Wife Phenomenon in Cryonics

http://www.evidencebasedcryonics.org/is-that-what-love-is-the-hostile-wife-phenomenon-in-cryonics/

Ironically, the few, non-hostile women attracted to cryonics seem pretty airheaded for the most part, except for the female co-author of the above essay whom I know and respect.

I read about Eratosthenes in Carl Sagan’s “Cosmos” and never forgot his story. Thanks for sharing this.

Have you been watching Cosmos, Quintus?

Good point about small observations leading to immense conclusions. I have a silly little hobby where I do similar things using mathematics to figure out the physics behind various happenings in fiction. For instance just by knowing the height of a character, and the proper place to scale from, you can figure out things up to the size of a planet (and thus how much energy in joules it would take to destroy, like the Death Star). Sounds pretty nerdy (it is) but it keenly helps your observation and logic skills. And it’s how I got good at math and physics. Hah.

It’s a famous story, and Sagan probably got it like I did, from books on ancient Greek science.

The only thing I don’t like about Sagan’s account of this famous story is that he makes it seem that Eratosthenes “discovered” that the world was a sphere. This is not really true. The sphericity of the Earth was known to Aristarchus and Hipparchus, who predated Eratosthenes. It was probably also known to the Babylonians, who made amazingly accurate calculations.

What makes Eratosthenes’s deductions so important is that he did so much with so little, and had the ingenuity to make big conclusions from simple observations.

I thought about doing this post on Archimedes, who was more of a genius, but I figured that more people already knew about the “Eureka” bathtub story of how discovered the principle of specific gravity.

If anyone doesn’t know it, he should check it out. It’s another great tale. Archimedes was hired by the King of Syracuse who suspected he was being cheated by a goldsmith who had made a crown for him. After some deliberation, Archimedes figured out that you could figure out the weights of the alloys composing the crown by measuring the weight of the water displaced when the crown was submerged. Great story….check it out. And the goldsmith?

He was executed.

I always enjoyed the story of Archimedes’ magnifying glass, used to set raiders’ ships on fire before they could land on the beaches.

Yeah, those stories were passed on by Roman historians. The accounts claim that he designed huge lenses and mirrors to focus the sun’s rays and burn Roman vessels trying to take Syracuse. I just don’t see the physics/optics working out on that.

I’m not sure I believe these stories…they sound apocryphal. But I do believe that he designed huge cranes and grappling hooks to smash Roman raiding vessels.

Regardless, Archimedes was the greatest scientific genius of antiquity and without doubt one of the greatest ever. He came within a hair of inventing differential calculus, and this was 1500 years before Isaac Newton.

Actually Sagan discusses Aristarchus, Hipparchus, and others, and mentions that it was known that the Earth was a sphere dating back to at least the time of Pythagoras in other episodes in the series.

marvelous

Somebody just watched Cosmos. Every single dude mentioned here was discussed by Carl Sagan.

Every single dude mentioned here is discussed just about anywhere. Even in your high school textbooks.

Correct…

Great article. I think Nietzshe was the one who said that we should treat an art exhibit as if it was a highly ranked officer officer – we should stand in front of it and wait till it says something to us.

This is a great post, and was a pleasure to read. Thanks so much!

There’s a story in the bible about two neighboring farmers dealing with a terrible drought. One farmer half-kills himself by plowing and seeding in the terrible heat, tending and expanding his plot of dusty soil, while the other waits patiently for the drought to break, with his seed, plow and ox ready to go. When the rains come, the exhausted farmer sits and watches his crops begin to grow, while the other frantically tries to seed and plow in the muck, missing some of the growing season and leaving half his plot unplowed.

While obvious, the moral of creating fertile ground for yourself rather than merely waiting for conditions to be ripe has always stuck with me. Every great figure, every great action, and every great reward has always come from careful investment in time, development of talent and brutal backbreaking effort. It seems, too, like every great figure like Eratosthenes carefully learned all he could from his peers and forebears, but was never limited by their limits, prejudices or preconceptions, and that’s a hell of a lesson too.

Fantastic article. Every one of your contributions is uplifting, classy and inspiring, dear Quintus.

I thoroughly enjoyed this Quintus. I wonder how many great and seemingly unreported discoveries were the result of the ‘why?’ mindset.

You are talking about logical INDUCTION for the most part here. Check out Dr. Leonard Peikoff’s work on the subject.

Fantastic, Quintus! Although I’m a ‘college grad’, your writings shed light on my poor education and ignorance.

I sit at your feet as a humble, appreciative, student.

Great article.

A similar post which covers the same topic: http://thelastpsychiatrist.com/2009/05/the_difference_between_an_amat.html

This article is an inspiring masterpiece. One of the very best things I’ve read anywhere recently. I’m spreading the word about this site.

All throughout reading the article I had only one question in my mind. Is there any woman in this world capable of doing what Eratosthenes did? The observation, the perseverance, the putting such disparate things together and drawing such a different conclusion from them… I think the answer is no.