Some men were just born for suffering.

Born needing it, like the dualistic relation between an essential Blood-Spirit and its purgative catharsis: mingling, mingling, and never quite coming together. So we have this great Spirit, this Blood-Spirit, driving us forward, and at the same time this purging, this cleansing, that goes on at the same time. The two forces coexist, and are bound up together. Complementing each other, but at the same time in opposition.

Think of Roosh stumbling through South America, escaping the tyranny of Dr. Wang and his little petri dishes, from the tyranny of being told to be “respectable”; and at the same time, being wracked by parasites and dystentery. Following the essential Blood-Spirit, and being purged simultaneously. It is a fitting dualism, if you can manage it.

And there you have it. The essential purging that must take place before our Mr. Roosh can be free of greasy Dr. Wang, free from mother, free from sister, from the oppression of familiarity, and free from Maryland. Ah, how he hated Maryland, how he yearned to get away. Away. To scrape off the old resin with a Roman strigil.

And so they writhe, such men. Myself included. Some men were just born to writhe on the edges of razors they themselves spend their lives honing. To flail at themselves with their Idealistic cat-o-nine-tails. Thwack! Thwack! You can almost picture Roosh scourging his back again and again with his flail, wishing for Poland, for Brazil, for Colombia, for anywhere but here. But why, why, isn’t he happy? Because he knows the Ideal is doomed.

Roosh’s Why I Can’t I Use A Smiley Face is the poignant confession of a man who has lived this great experience for us, this experience of exploring foreign lands in search of the great female “Paradise”. Confessio pro vita sua. Poosy Paradise, as he calls it. The Great Snatch. The Pink El Dorado. And he returns to the US to find mostly grimness and disillusionment. To return home to get winks from 50 year single mothers on Match.com, to be condescended to by fat, arrogant dunces who nod politely and understand nothing. And so Roosh goes on flagellating himself. Thwack! Thwack! It is an entirely necessary flagellation, a required ritual.

And this is as it has always been, maybe. For it has been the fate of every real traveler—not your run-of the-mill Lonely Planet tourist–to return home to the maddening incomprehension of the common man. Don’t believe me? Look at what Melville, Richard Burton, and Wilfred Thesiger endured. Outcasts. The boorishness of the mob. The stupidity and inertia of the masses. Or think of Marco Polo, clapped into prison when he returned home for spinning what his countrymen called “tall tales”. Literally. Seems the Venetians didn’t like what he had to tell them. Didn’t want to hear it. Or Melville. Living among the South Sea Islanders, frolicking with Fayaway, on a different planet basically, and then coming home to face decades of disillusionment as a hack and occasional customs agent in New York City. With heating bills, a wife he hated, and a drunkard son. Anguish. He was another one born to suffer.

Well, our Mr. Roosh is right, of course. Society truly is a hateful place. The culture here is as soul-gobbling and rotten as he imagines it to be. Maybe more. You have only to enter any megastore in suburban America to view a species of humanity that barely qualifies as human. Homo corpulensis degeneratus. Walmart. Target. Home Depot. Take your pick.

But we are the agents of our suffering, mostly. Because it is we who construct the Great Ideals in the first place. The Great Ideal. The ideal of the Perfect Woman. We set ourselves up for disillusionment. The ideal of the perfect relationship. By persisting in our Ideals, we condemn ourselves to writhe on the edge of our own straight-razors: for there is no perfect woman, no perfect love, no perfect relationship. Melville tried and persisted in his Idealism, and went to his grave trying. He never quite recovered from his stint among the cannibals. He searched for the perfect love and couldn’t find it: his Polynesian mistress could never measure up. Searched for the perfect friend, and couldn’t find that either. His friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne could not meet his Ideal. Nothing could, really. Because there is no Perfect Ideal. Because there is only struggle, and fight, and struggle some more. And this is life. Pass me a drink.

And yet there is something great and noble and savage in this confession, this little testament of Roosh. This noble confessio. Because in his heart, Roosh remains a proud soul: an expression of the purest Dream-Quest. The great odyssey in search of the Great Ideal: the great Arthurian quest. And there is something stirring and redeeming in that. For its own sake. The quest itself redeems, does it not? The Ideal itself redeems. Even if it is doomed. Compare the noble and doomed love of Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra to the unmanly whining and cringing of King Lear, shouting to heaven at the injustice of the world. You tell me which is more noble.

Because no matter what, our Roosh knows he is not going back to Dr. Wang and his test-tubes and his petri dishes. Ah, how he despised little greasy Dr. Wang and his rules, and how he ached to get away. To escape that prison. Away! Away! Anything to get away! And he did get away, he did indeed. He split from the whole program.

It is a noble confession because he never lost hope. Roosh never could abandon himself to despair or indifference. He never gave up. Even when he says “enjoy the decline”, don’t believe him. Don’t believe a word of it. It is his unconscious way of dodging his real sentiment. He isn’t enjoying the decline. He writhes with it. Because he cares. In truth, he loathes the decline. Like he despised old Wang and his petri dishes.

And this, the savage nobility of caring, is what makes him elevates him in the end. This is his Great Redeemer. The selflessness of the act of caring. Our Roosh, the great carer. The exterior he adopts–the acid, the profanity, the vitriol, the sarcasm–is his way of masking the essential gentility and nobility of character within. Of masking the purging of his Blood-Spirit, of masking the scars of the flagellation. Thwack! It is an armor of old date, a necessary protective coloration. Because Roosh doesn’t really want a private purging, a private flagellation. He wants and needs a very public one, a public catharsis. An auto-da-fe for Mr. Roosh.

For by living this great experience for us, he has effectively shed his old skin, reptile-like, and has started to grow his new skin. His new identity, his new essence. It is a painful, agonizing process: like being reborn. The process of being reborn, if you will. Because a new Roosh is taking shape before our eyes.

It is a great confession. Because Roosh knows in his deepest soul that the Ideal is doomed. His old Ideal. He just knows it.

Doomed. But yet he refuses to abandon his Ideal. His Titanic-like Ideal is going down, down beneath the waves, but he continues to fight. And he stays true to his own noble Blood-Spirit. His deepest identity. And this is what redeems him, and will assist him in his new Rebirth. His new mission, his new Ideal.

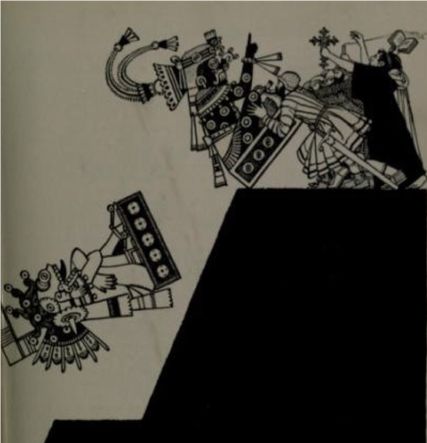

Because sometimes we have to grind ourselves down, to shatter our old icons, to shed our old skins, before we can be reborn. When the old Idols no longer serve the purpose for which they were created, they must be overthrown. We must scale the steps of the pyramid, smash the old Idols, and roll them down the steps. Destroy them utterly. As Cortes pulled down the dead gods and dead idols in Tenochtitlan. Well, let the old gods die. Good riddance.

O, how I long to point my howitzer into the faces of the Old Idols, and pull the lanyard! Fire for effect! For only then can we be reborn. And begin anew.

Read More: The Man Who Dropped Out Of Harvard To Become A Sailor