Governments, be they enlightened or otherwise, generally provide justifications for their rule. Despotic regimes don’t really need rationales beyond “We’re in charge, obey or else“. However, in practice, even tyrants go through the motions. A “People’s Democratic Republic” might not quite be a bastion of freedom, but they’ll sure talk a good game of it. The notion of legitimate government has its uses, even when reduced to a myth.

In ancient days, the rulers (kings, nobility, and priests) led society. The warriors were below them, carrying out the nation’s first duties: to defend the people and keep public order. The producers (everyone else) formed the third class. Plato wrote the book about this tripartite top-down structure. Modern scholarship has noted that this was universal in Indo-European societies. India developed it further yet.

The concept of legitimacy argues that a regime has moral authority, while discouraging backstabbing and promoting obedience. The ruling class must believe the king deserves the job. The warriors must obey His Pudgy Majesty’s officers unquestioningly, and not contemplate regime change. The producers must remain motivated to keep working, obeying the law, and paying taxes.

Despite this cynical perspective, the tripartite arrangement works. It’s essentially how all countries function. The degree of freedom—from the Libertarian ideal to an Orwellian dictatorship—all depends on how it’s implemented. No alternatives exist, other than half-baked utopian schemes like anarchy.

Legitimacy in history

Among cavemen, the strongest hunter probably called the shots. Thrasymachus in Plato’s Republic argued for that harsh pragmatism. When tribal societies emerged, the chief was a hereditary job.

During the dawn of civilization, nations were emerging. Agriculture began providing a fairly steady food supply for the masses. People figured out how to bake clay into bricks and stack them together. City-states in Egypt coalesced into the northern and southern kingdoms, and by about five thousand years ago, they united under a single Pharaoh. Around the same time, Mesopotamia and China came onto the world stage. Other nations arose over the centuries, all ruled by monarchs who amassed great wealth and power.

This presented a particular problem. Imagine a peasant villager talking politics: “We’re dirt farmers living in mud huts. Meanwhile, the King lives in this huge palace with golden furnishings. He has dozens of wives, concubines, and slave boys. He makes lousy decisions and taxes our loincloths off. This incompetent weakling hasn’t worked a day in his life, and his toadies are no different. Really, what makes this douchebag so special?”

The ruling class needed to give the public a compelling reason to kiss their asses. Sometimes “obey or else” isn’t enough.

Divine right

Early on, some rulers set themselves up as deities. This wasn’t discouraged by the priestly class that also rode the aristocratic gravy train. This didn’t mean the monarch could pull off cool stuff like walking on water or levitation. However, what mattered was the public at least paying lip service to the notion.

The Egyptians took it pretty seriously back in the day. The Romans knew the Imperial Cult was baloney, but still had to go through the motions, a major sore point in monotheistic Judea. During heathen times, the Anglo-Saxon kings sometimes traced their lineage to divine ancestors. After all, who dares challenge Woden’s great grandkid?

During Christian times, that stuff didn’t fly any more. So the story changed: kings ruled by God’s will. To obey the king—even if he was a royal asshat—was to obey God, and rebellion was a sin. The Catholic Church certainly encouraged this message, and also had significant political power. To symbolize divine sanction, bishops and sometimes Popes presided at coronations (though Napoleon spoiled the party). Biblical references like the following encouraged the notion:

And he changeth the times and the seasons: he removeth kings, and setteth up kings: he giveth wisdom unto the wise, and knowledge to them that know understanding:

—Daniel 2:21

This leads to a conundrum. This concept of divine destiny means that God put fruitcakes like Ivan the Terrible, Idi Amin, Kim Jong Un, and Justin Trudeau in office. Couldn’t God pick better leaders? In contrast, in the Chinese concept of the Mandate of Heaven, divine approval is contingent on the rulers acting responsibly.

So throughout this time, legitimacy meant that the king would be the eldest son of the previous king. How did the dynasty’s first king get in charge? Usually he was whichever chieftain last took over the place. Saying it’s all God’s will sounds much better.

Popular sovereignty

Militant radical extremists in 1776

Age of Enlightenment philosophers came up with several new ideas, such as limited government, separation of powers, the rights of man, and rule by the people. Democracy existed at times in ancient Greece and Rome, but otherwise was largely unknown for centuries. By this standard, legitimate government means that the people are in charge.

The early USA’s success showed that representative government could work. The electorate now chose their rulers, directly or indirectly. Religion (the updated priesthood) was still a powerful force in the moral sphere, but lacked political control. Meanwhile, government stayed out of their hair. Following this proof of concept, eventually kings were deposed or reduced to figureheads. By the mid-20th century, monarchy was washed up, with the sole major exception of Saudi Arabia.

Those preferring “throne and altar” traditionalism consider the Age of Enlightenment a big mistake where everything started going to hell. Granted, monarchy had some positive attributes, and made sense when commoners were mostly illiterate. Back then, lords were lords and peasants were peasants, but nobody was an atomized consumer tagged with a damn Social Security number and spied on nine ways from Sunday.

Still, we needn’t throw out the baby with the bathwater. If done properly, representative democracy has clear benefits. The people have investment in their government. Bad politicians can be voted out. It’s regime change without all the hassle, at least theoretically.

Ideological government

During the 20th century, Communism and Fascism emerged as major players. In a way, these were the realizations of Plato’s “philosopher king” concept. In Communism, legitimacy means the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. (The Party defined itself as the Will of the People, naturally.) Fascism is basically populism on steroids, with the nation’s interests in first place. Both had big government strategies, ham-fisted propaganda, and lousy human rights records. All this was considerably more so for Communism in actual fact, though Fascism has a worse reputation for fairly obvious reasons.

The fortunes of war were the downfall of Fascism. Perhaps better diplomacy could’ve avoided this, though opposition from the League of Nations made this difficult. Also, globalism was emerging, which opposes nationalism. The downfall of Communism was their goofy economic system. Former Communist nations still struggle to recover. Neither ideology remains a major player in pure form. However, both inspired some derivative ideologies, some better and some worse.

Globalism

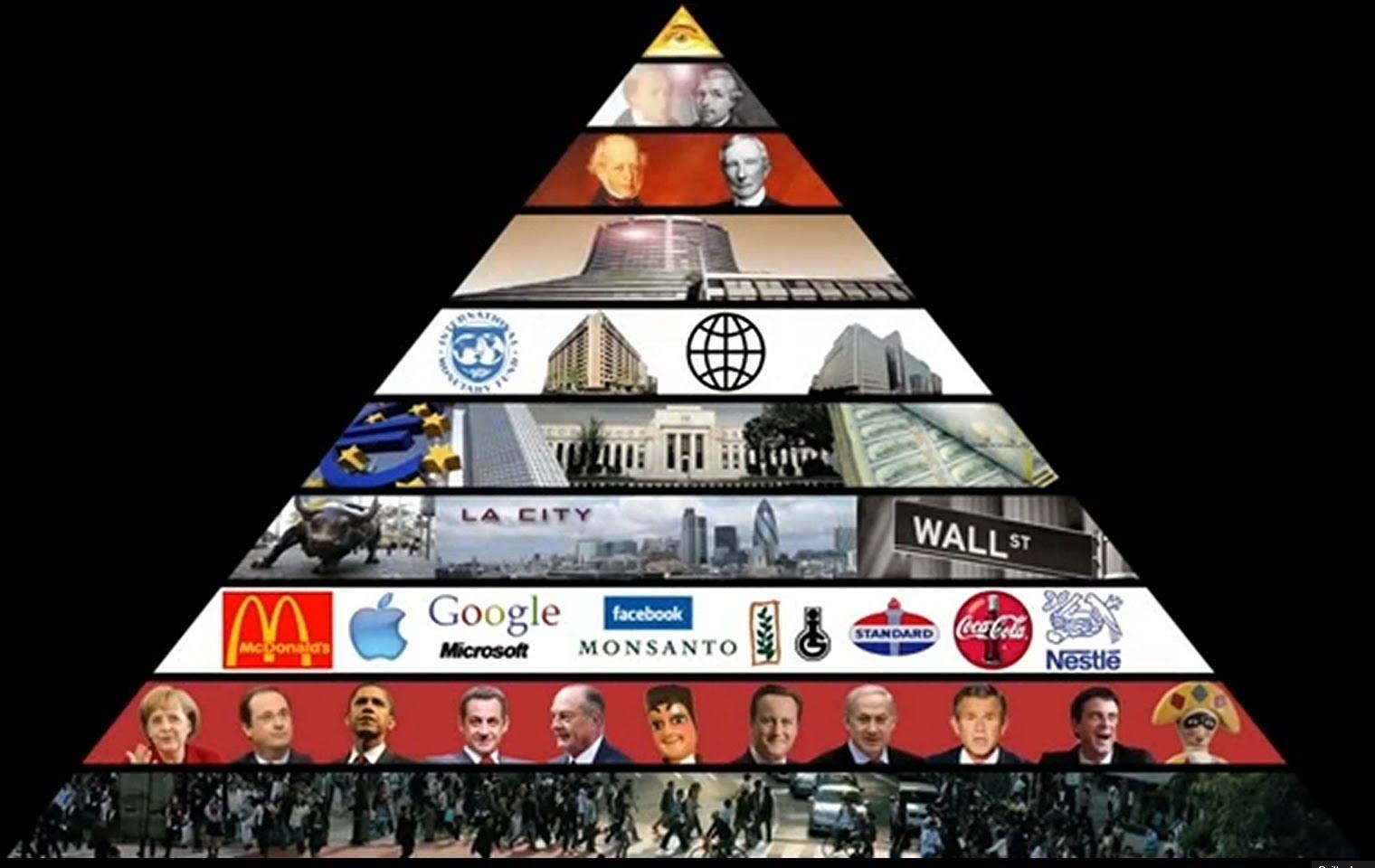

Business interests tampering with American statecraft is nothing new. However, the most prominent powerbrokers form an international clique. During the early 20th century, this ultra-wealthy coterie attained great power.

Surprisingly, they were fairly chummy with Communism despite the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” business. Some even wired the Bolsheviks heaps of cash during the Russian Revolution. In the USA, they were quite influential by FDR’s administration. Eventually they had their fingers in both major parties and the Deep State. One small example of “Shadow Government” influence is Wall Street selecting Obama’s Cabinet.

As for religion, its influence is greatly diminished from times past. However, the mass media—The System’s propaganda arm—takes its place. The celebrities and pop culture figures it promotes are its priesthood. Most are nauseatingly leftist (or at least know who signs their paychecks) and serve the power structure headed by the globalists. Academia also fills a priestly role, lending some gravitas.

A surprising number of prominent figures have spoken glowingly of the “New World Order”. The public considered this as sinister as hell, so euphemisms were substituted, like “global governance” and “international cooperation”. The goal is to erase borders gradually. In practice, this means free trade, mass immigration for population replacement, and transferring sovereignty to unelected bureaucrats. However, the way they describe it sounds pretty darn warm and fuzzy.

Plutocratic billionaires pull strings behind the scenes by buying politicians, a hazard of the open nature of democracy. Their favorite hobbies are social engineering, subverting governments, and golf. Unfortunately, many of our would-be rulers are sickos with a God complex. Worse, they’ve settled on cultural Marxism for a ruling ideology, and practice its script of continual destabilization. They live like kings and seek to make everyone else peasants.

They’ve subverted our society’s legitimate basis of government. Managed democracy is not democracy. What right do they have to do this? Really, what makes these douchebags so special?

Read More: How A Small Cabal Is Using Socialism & Cultural Marxism To Consolidate World Power