I’ve spoken about the limits of feminism before, but today I’d like to explore them further.

Feminism, as a whole, is not without some wide appeal. Women almost everywhere, for example, could get on board the whole “equal pay” train, and most would also agree with many feminist points relating to the evils of domestic violence and the like.

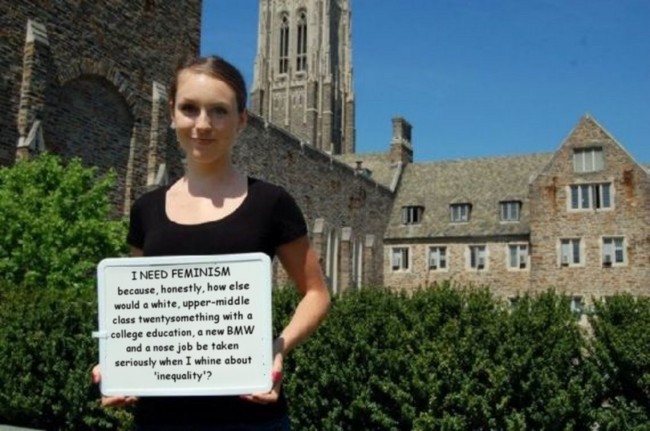

The core of modern gender feminism (the variety that you and I will most regularly encounter in western society today), however, is one that is fundamentally tied to the wishes and desires of affluent, white, western women above all others, and one that privileges their concerns more than anyone else’s. I shall explain why this is.

The Core

To understand this, it is necessary to dive into the very depths of feminist history.

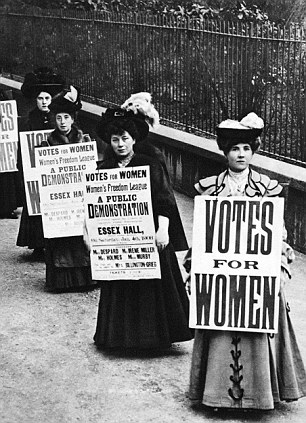

The core of the feminist movement is its opposition to “traditional gender roles”. Feminism began as a movement built by affluent western white women (most of whom were firmly restricted to domestic life) in order to challenge the notion that a woman’s place was in the home and nowhere else. It sought to show that women could be successful outside the home as professionals and thinkers, while also making the case that women could and should have an equal say in matters that go on outside their kitchens (e.g., the right to vote).

The thing is that these problems are, for the most part, white ones, specifically white western ones. Whereas western white women fought during the first and second waves of feminism to carve out roles outside the home, black, Native American, and even many Asian women have held such roles within their respective societies for centuries.

A Difference In Labor

In Africa, women had long labored outside the home. Whereas European gender roles often restricted women from performing labor crucial to society’s sustenance (e.g., working in the fields), African women had long played a crucial role in their society’s economic sustainability, performing extensive fieldwork and other indelicate but necessary chores. This was true long before slavery, and is still true to this day. They, unlike European women, exerted direct influence on the production and transport of food and in other forms of labor. African women have long been expected by their men to have some sort of say outside of the domestic realm.

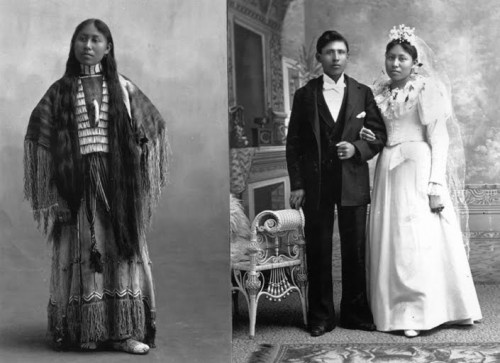

Native American women (ancestors of the majority of Hispanics we know today, for the record) were doing the same thing. It was very common throughout Native America for women to perform all kinds of agricultural and other forms of manual labor in their communities.

When you study the “civilizing” missions attempted by Anglo-Americans in Native American societies during the 19th century and examine documents like the Lewis and Clark Journals, you’ll see that this was a key bone of contention among Anglo-Americans looking to find solutions to the Indian “problem” as they saw it.

The fact that Native American women were performing actual labor was considered by white Americans to be evidence of their savagery. Meriwether Lewis thought it ridiculous that Native American women he met were sometimes seen performing acts of “drudgery” he considered improper for women, and took this as a sign that Native cultures did not respect their women. Most Europeans agreed with him, and would for centuries after he made his journey.

You would see this emphasized in American Indian “education” policy, whereby Native Americans were forced onto reservations or into boarding schools to be “civilized.” This civilization was based on the notion that they would adopt traditional European gender roles—their men would stop hunting and start farming, while their women would stop farming and start sewing.

Black women in the Americas, like Native Americans before them, spent centuries during and after slavery working outside of what Europeans would consider “traditional gender roles.” White western women were often shielded from serious work and protected in the home—these same women would be the ones to kick off the feminist movement and begin asking for more responsibility outside the home.

Black women already had this, as did Native American and some South Asian women. From a “feminist” perspective, Europeans actually brought Native American and African women backwards. They were already “liberated” from restrictive cults of domesticity—they did not need affluent white women to tell them how to find this liberation.

A Difference In Family Structure

Many African women also lived in matrilineal societies. Whereas European women long existed in a society that saw their marriage to a man as essentially a forfeiture of their economic and social independence, African women could maintain much of this due to matrilineal organizations that gave them greater control over family life and their children’s future.

The same was true of Native American women. In many Indian societies, it wasn’t uncommon for the father’s line of descent to prove somewhat inconsequential to the actual status of the child, a reality far removed from European norms that conveyed status largely on the basis of the father’s name passing to a child.

Differences In Male Dominance

Feminism also called for an end to the patriarchy and the dominance of men over women, an initiative that still animates the movement to this day. The problem, of course, is that the “patriarchy” referred to there simply hasn’t persisted in every society.

Black men, for example, haven’t had true dominion over their women for centuries. In Africa, the black man often had polygamy and certainly plenty of authority, but he also often dealt with matrilineal lines of social organization that limited his dominion and influence over his women and progeny.

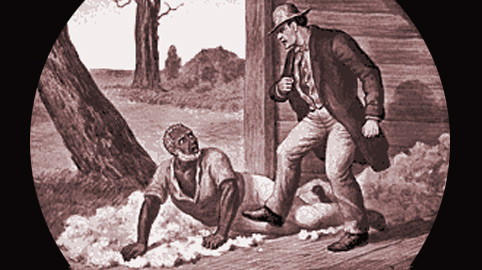

In the new world, the black man was essentially a pack horse for his first several centuries. He had no real power to keep his family together (it could be split apart at anytime should a slave owner choose, often deliberately), and he also had no power to guard the sexuality of his women. He had no status or influence relative to the white men who took near undisputed dominion over the sexual capacity of the black female.

White men kept black women as mistresses or concubines and quite frequently impregnated them with very little opposition from black males who, frankly, could do nothing about it. Black men had no real power to stop their wives, sisters or daughters from being used in this way or sold indiscriminately. They had no control over black female mobility or sexuality.

Thus, when white women (over whose sexuality white men did maintain some control) come out and complain about freeing themselves from the “oppressive” control their men had over them, it becomes difficult for blacks to interpret things in the same way. Black men have not historically controlled black women in that way.

Black men also have not prevented black women from seeking roles outside the home in large part due to economic reality. Black males, unlike their white peers, didn’t have the money to fund the stay-at-home mom lifestyle so many white women felt “oppressed” by during the mid-century prior to the second wave feminist explosion in the sixties. While white women were reading “The Feminine Mystique” and ruminating about the “oppressive” nature of their role as pampered suburban housewives, black women were working in what were usually less than ideal conditions.

So how can black women adopt this white feminist narrative regarding the “patriarchy”? They can’t, really. Neither can Native American, Hispanic or even many South Asian women. That narrative comes from a (usually well-off) white woman’s perspective, and other groups simply haven’t had the same experiences.

The Eastern European Model

It must also be noted, lest you think this is strictly a white vs. non-white dynamic I’m trying to establish, that many Eastern European white women of today can’t adopt the western feminist narrative either because communism also saw them “liberated” from traditional gender roles.

While white women in the UK and USA were busy talking about their oppressive restriction to the home and their desire to do all the things men can do, Soviet women were on the frontlines putting bullets in German heads. Eastern European women were entering male realms of society (serving as combat pilots, combat troops, tank gunners, and also working in factories even after the war) earlier and in greater numbers than women elsewhere. The same was true, to some extent, in Communist China.

Thus, when white western feminists started going on and on about the need to be liberated from “traditional gender roles,” you could imagine that such calls may have had less pull in the east. These women had already had a greater taste of such “liberation” than any western white women at that point, and possibly greater than any western women have today (how many females do we have serving as frontline combat troops in the US military?). They simply did not have the same urgent need for that narrative, and many have probably already learned enough about it through experience to know that it has serious pitfalls.

To these and other women (Africans, Native Americans, and some Asians), traditional gender roles might not even seem quite so harmful. Some may even associate less traditional roles with oppression and/or racism. Black women, for example, could argue that they were forced outside of more traditional European gender roles due to racist limitation of black male earning potential, arguing that white female status as housewives within older cults of domesticity was actually a sign of privilege. To them, the white western feminist perspective is simply not as easy to understand, much less fight for.

Western gender feminism as we know it today is a middle/upper-class white, western female phenomenon. Its focus on minimizing the value of traditional gender roles and on the promotion of unrealistic gender equalism is founded on the status those women have historically enjoyed as the most well-protected, pampered, adored, and privileged women in history, and it is designed largely to serve problems that resonate with that experience. Other women can have “feminisms” of their own to address problems they face, but they would be fundamentally different from the kind of feminism we most commonly see here in the west.

Read Next: Modern Woman In Wanting To Be For Herself, Has Destroyed Herself