Plutarch’s Life of Aristides contains a compelling aside about the perfectibility of a leader. What he calls the “divine nature” of a great man has three attributes: power, virtue, and immortality. Of these, virtue is the most important; prestige must flow from it primarily, rather than from the uncertain reservoirs of violence or power. Continuing in this vein, he notes:

So when we consider the three sentiments, admiration, fear, and reverence, which divinity inspires among mankind, we find that men appear to admire the gods and think them blessed because they are immortal and unchangeable…At the same time men long for immortality, to which no flesh can attain, and for power, which remains for the most part in the hands of fortune, while they give virtue, the only divine excellence of which we are capable, the last place in their scheme of values. [Life of Aristides, 6]

And it is here, he says, that we show ourselves to be fools, since justice comes from virtue. And the authority of a great man “still needs justice to make it divine.” Power unsupported by justice and virtue is savagery; it corrupts him who wields it, and brutalizes him who is fated to endure it.

Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello, known to history as the Marquês de Pombal, was the most powerful man in eighteenth century Portugal. Born in 1699, he was the son of a county squire whose piety exceeded his means. He saw to it that his son received a Jesuit education; a subsequent period of military service taught him the means and ways of authority. Marrying into a family of noble affiliation, he used his opportunities to advance a political career, and by 1739 had achieved a foreign ministerial post in London.

Study of English political institutions opened vistas of possibility for him on how ecclesiastical authority could be subordinated to temporal power; and it was here that he first likely began to imagine a Portugal free from the ancient shackles of clerical control. What Henry VIII had done in England could, perhaps, be duplicated on the Mediterranean. These sentiments he did not disclose to anyone.

With clerical support, principally from the Jesuits, he secured an appointment to the cabinet of King Joseph I in 1749. His energy, industry, and will distinguished him from his contemporaries, and he soon came to dominate the king’s ministries. Yet whisperings of disapproval of his ignoble birth continued to vex him, depriving him of the unqualified support of the aristocracy, for which he nursed a covert hostility. The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 confirmed his indefatigable energy and brusque confidence.

The earthquake, with its accompanying fires and tsunami, devastated the city. Desperate mobs of looters swarmed in to pick over its heaps of rubble. Joseph granted him nearly dictatorial powers to deal with the crisis. Pombal ordered soldiers to occupy the city and shoot looters on sight; for the dazed citizenry, he instituted price controls, established relief camps, and began an energetic reconstruction program. Modern Lisbon is the product of his applied renovations.

Portuguese civil society in his day was heavily dominated by clericalism; education was nearly entirely in the hands of the Jesuits. The Inquisition still operated as a state-within-a-state, controlled at least nominally by the Vatican. In commercial relations, British companies wielded an undue influence.

For a man of Pombal’s nationalism and stubborn pride, such a situation was intolerable. Echoing the sentiments of Richelieu and Henry VIII, he believed that the road to modernization must begin with the subordination of church to state. He would bring the Catholic Church to heel. To this task, he now turned his obdurate and ruthless stamina. He harbored no doubts that he was acting in his nation’s best interests.

The Jesuits proved an easy target. Under the terms of a treaty negotiated with Spain in 1750, Portugal acquired seven reductiones (settlements) in Paraguay near the Brazilian border, on which the Jesuits had organized Indians in self-supporting communities. The treaty required the removal of the Indians, then numbering about thirty thousand; and when the Indians resisted their eviction, with apparent Jesuit backing, Pombal turned against the Society of Jesus with a pitiless ferocity. He now sought nothing less than the removal of Jesuit influence from Portugal’s commercial and civic life.

But the Jesuits were as subtle as he was ruthless; they caught wind of his intentions, and plotted his overthrow. Their leader in Lisbon, Gabriel Malagrida, was a man of devout conviction and patient subterfuge; he sent out feelers to aristocratic families in the capital who shared a desire to remove Pombal, the upstart dictator of lowly birth. Joseph I, who by now was nearly Pombal’s instrument, was coaxed by him to believe that the Jesuits desired to replace Joseph himself.

With successive edicts, the Jesuits were gradually purged from Lisbon’s commercial circles; Pombal even incited opposing cliques in the Vatican against them. A failed assassination attempt against the king in September 1758 ended whatever doubts Joseph may have had about Pombal’s direction; he now gave his minister unqualified support for the anticlerical program.

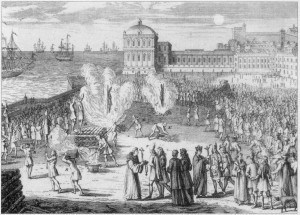

The attempt on the king’s life was now used as the pretext to arrest and put to the torture a number of prominent aristocrats and Jesuits, including Malagrida. There was some evidence of a loose conspiracy, and nine nobles were publicly executed early in 1759. Pombal explained his actions in widely circulated pamphlets; sentiment against the Jesuits ran high in Europe. Pope Clement XIII argued for moderation against the Jesuits, noting their record of productive works and protesting that collective punishment for the misdeeds of a few was unjust. But by now, Pombal smelled blood, and pressed his advantage.

He had royal orders issued which confiscated all Jesuit property in Portugal, and mandated the expulsion of all Jesuits from the kingdom, as well as from Brazil. To make certain that Clement in Rome got the message, relations with the Vatican were severed in 1760. Not since the destruction of the Knights Templar by France’s Philip IV in 1307 had Europe witnessed such a brutal repression of a religious order.

Deprived of all possessions except their clothing, columns of haggard Jesuits made their way to port cities in the Algarve for expulsion to Italy; many had been reduced to destitution by the hardships of the deportations. As the public watched with mounting unease at these cruelties, opinion slowly began to turn against Pombal and his government.

And yet, as these whisperings of dissent grew, he arrogated to himself full dictatorial powers with Joseph’s blessing. The list of arrestees grew year by year; agents and informers proliferated; and aristocrats and clerics from all over Portugal and the colonies were clapped into jail for the slightest expression of opposition to the despot.

As his insecurity grew, so did his isolation and his arbitrariness. Prisons were stuffed with noble inmates, with many of these left to rot in detention for years. His old enemy Malagrida was finally brought to trial and condemned to death on trumped-up evidence after years of imprisonment; an old man of seventy two, he mounted the scaffold in 1761, utterly broken in body and spirit. Voltaire called the execution an act of “the most horrible wickedness.”

His enemies nursed their hatreds in seclusion, and prayed for his downfall. The dictator’s methods had laid a black hand on nearly every aristocratic family in the land; and abroad, Europe’s elites, initially sympathetic to his attempts to modernize Portugal, were horrified at his excesses. His orders to burn the village of Trefaria for its resistance to his military recruiters confirmed him as a man who had now completely abandoned any pretense of decency.

The death of Joseph I, Pombal’s patron or puppet, in 1777 marked the beginning of his downfall. Immediately after Joseph’s burial, the new regent Maria I ordered the release of over eight hundred imprisoned Jesuits and aristocrats from Pombal’s dungeons; public outrage swelled as word spread of the extreme state of their physical deterioration. The natural piety of the people reasserted itself. The tide had turned against Pombal.

Some prisoners, having languished for years under fraudulent writs, refused to leave their cells until their innocence had been publicly declared. Pombal was now unable to show himself in public. He tendered his resignation to Maria and was allowed to retire to private life, despite calls from her court attendants for his arrest and prosecution; forced to slip out of Lisbon in secret, he was nearly attacked by assailants.

He was now an old man of seventy-seven. Because he had been cunning enough to have his edicts issued under the late king’s signature, he could not be easily prosecuted by Maria, the daughter of Joseph I. Yet he was hounded day and night just the same. Lawsuits and inquests accumulated; a panel of judges interrogated him for days on end until he nearly collapsed in exhaustion. The families of his political victims swarmed over him as a cloud of angry wasps. So the cruelties of the wicked are, by the humor of Fortune, turned back against their perpetrators. As Seneca tells us,

As weapons drift away and intrigues cease,

The mighty flounder under their own weight,

And fortune vanishes, as itself a heavy burden. [Agamemnon I.85]

Many of those he had imprisoned were now exonerated, with their property and reputations restored by Maria. She officially denounced him as a criminal in August 1781; but to spare the country, or her family, the ordeal of a trial, she took no further action against him. He was not long for this world in any event. Some wasting disease had engulfed his body, covering it with lesions, and denying him the simple pleasures of rest and eating. His agonies came to an end on May 18, 1782.

He had aimed to modernize Portugal, and subordinate its clerical establishment to the crown; and in commerce, education, and foreign policy, he had overseen some modest successes. Yet his rashness and hubris had undone him: unable to control his passions, he had permitted himself to be consumed with hatred for the Jesuits, the aristocrats who had impeded his career, and finally, anyone who breathed a word of dissent against him.

He had sinned against his people, disrespecting their traditions and forcing on them an anticlerical program that was alien to their nature. He was once the ungrateful favorite of mistress Fortune; but as his impieties accrued, the insulted goddess revoked his privileges, and pursued him vengefully. In the end, it was not his enemies, but rather his own hubris, that proved to be his undoing. Fortune’s day of reckoning with the insolent, the grasping, and the proud may be intermitted, or it may be adjourned, but it is never cancelled.

Read More: The Visionary War Photography Of Alexander Gardner

Good article, hubris is one of the greatest weaknesses of man yet it is something that quite frankly many men would find hard to resist. With excessive success and an accumulation of power many men begin to “drink their own kool aid” so to speak. However I would argue that hubris in of itself is not as dangerous as the inability of man to look past his own mortality. For example Alexander the Great was as prideful as one could be and accomplished much more than any man in his day and age, yet it was his inability to heed his own mortality and cultivate a successor that led to the eventual disintegration of all that he built not long after he was gone. Likewise Marquis de pombal knowing his advanced age would have done well to instill his vision into someone who could have carried it forward even after his eventual removal from the scene either by force or ultimately death. I am sure there are many more historical examples in this regard.

Hubris..

yes every time I think I got it in the bag 6 months later I have every reason to be curled up in a corner and suck my thumb.

It’s gotten so that I’ll not even allow myself to be happy because the minute I do, it’s as if some alarm sounds in God’s office and they have to fuck with me.

Man must not ask for too much fortune lest hubris befall him nor too little that he may be trapped in a cycle of victimhood and self-pity or turning to crime or parasitism to survive his pitiable state.

Haha, good insight. I have also noticed that celebration is all too often the beginning of the end of a winning streak.

VDH–“Nemesis: She is the dreaded goddess who brings divine retribution in ironic fashion to overweening arrogance.

“Headstrong tragic figures neither welcome in critics nor would listen to them if they did. They impute their unforeseen temporary success to their own brilliance — and expect it to continue forever. So would-be gods set themselves up for a fall far harder than what happens to the rest of us…

“What are we left with? The daily struggle to remember [sumus homines, non dei] — ‘we are just humans, not gods’… The common denominator is arrogance and a sense of exemption from the rules and protocols.

“In a word, human nature as we understand it from the earliest observances of the Greeks. Be careful about lecturing others on their moral frailties. If one consumes well beyond what one needs, ensure that one pays one’s own tab and does not indulge on someone else’ money. Beware of Nemesis, an omnipotent, all-seeing deity that marks in her scrolls every pontification, every sermon we make and then collates such profession with our deeds — so eager to note the discrepancy. She is an unforgiving goddess, and perhaps a cruel one as well. I used to giver her a prayer for exemption at her temple at Rhamnous.

“In the end, we are left with the nobility of hard, physical work, the elemental reality of producing food, fuel, and durable goods, the distrust of fad and cant, the acceptance that we are fallible and age and will not get out alive. In comparison, the media hype, the DC apparatchik, the eco cons and the high-life socialism are as nothing. ‘Know Thyself’ and ‘Nothing Too Much’ were written on the architraves of the temple of Apollo at Delphi, and for good reason, to remind us where we came from and who we were, and to shun excess — material, emotional, sexual. My grandfather’s (a man who at one time in 1936 housed 27 relatives in my present house) advice of 1970 to a smart-aleck, silly teenager still resonates to me: ‘Never sell this small piece of land, you may need it some day as a refuge from what you don’t wish to become.”

Men are only mortal. Men are only vulnerable. Unless one is Almighty God himself, he is always in same way defeatable for he is finite.

Excellent story (and article). I especially like the quote towards the beginning.

Thanks, Tim. I like these sorts of stories, as they help remind me of what is important in life.

Great work. Really a solid insight into the leverage that the Jesuits had over the Iberian and in large to the Iberians benefit. I’m surprised that Pombal didn’t recognise that Henry the VIII and Cromwell were essentially backing the aristocracy in their own country rather than the ones of the Vatican to get popular support among the aristocracy.Whereas the jesuit’s in the Iberian were essentially the old guard aristocracy that controlled and built the country. In modern times Spain and Portugal never really developed in the same fashion as the Anglo-Saxon countries because there was no real imperative too when the aristocracy still had a large hold over the mining and agricultural hold in South America. Where as when America fell to independence at a similar time there was a real push towards industrialisation as a means of preservation in Britain.

You have a solid grasp of history and the issues, Fisherking. And I like to see that.

thanks. it’s also worth noting how the Jesuits in many ways restricted the wealth transfer to the Vatican. The leader of the society of Jesus was always termed the “Black Pope”. Pope Francis was the first Pope from the Order and will likely be the last for some time. The early Jesuits were all essentially Jewish and some Moorish Islamic who converted to escape persecution (especially St Ignatius )and functioned as such with a strong emphasis on education.

Very interesting. Thanks for writing and posting.

Quintus, I very much enjoy your articles analyzing historical people and events. They are interesting, well written and never dissapoint. Keep ’em coming!

Thank you, Edmond. I’m very glad to hear that.

This has to be the best blog ever. Great post, Quintus. The Word says,

Proverbs 19:10 Delight is not seemly for a fool; much less for a servant to have rule over princes.

Stick the shiv into the beta id, as Roissy would say…

Proverbs 30 (21) For three things the earth is disquieted, and for four which it cannot bear: (22) For a servant when he reigneth; and a fool when he is filled with meat;

Never give a sucker an even break.

But, relevant to your post: could this man have been considered a “servant”, or is the son of a country squire considered to be close enough to nobility to merely be guilty of hubris. Did the King of Portugal violate the “don’t let a servant rule” rule.

Quintius Curtius should be teaching in Ivy League schools.

I have my moments, Dom. Thanks for the kind words.

*Slow clap*

A thoroughly informative and highly enjoyable article aka pornography for the intellectually inclined. This is a nice respite from the usual “gaming females” articles i see on here, i hope to see more like this from you in the future, Mr Quintus.

“He had sinned against his people, disrespecting their traditions and forcing on them an anticlerical program that was alien to their nature. He was once the ungrateful favorite of mistress Fortune; but as his impieties accrued, the insulted goddess revoked his privileges, and pursued him vengefully. In the end, it was not his enemies, but rather his own hubris, that proved to be his undoing. Fortune’s day of reckoning with the insolent, the grasping, and the proud may be intermitted, or it may be adjourned, but it is never cancelled.”

If God is my witness, this will be the wikipedia entry of barack obama circa 2050

“Fortune’s day of reckoning with the insolent, the grasping, and the

proud may be intermitted, or it may be adjourned, but it is never

cancelled.”

Let us be active agents of fortune against our own society’s versions today. Once power reverses, it reverses with a whirlwind.

Also I’m gonna say something that might be unpopular and contrary to my alias: a ruthless, cynical dictator like Pombal may be needed every once in a while, possibly for a free society to function in the long run. A man like him would quickly end this societal degeneracy.

Certainly true, in some situations.

The problem arises when they fix the problems, but never leave…!

Great read Quintus. Just got your book and looking forward to it. Thanks again!

Thank you, Aphex.

I really enjoy your articles. They bring a sense of class and elegance to this site.

Thanks, Quintus. I’m not sure his is a case of hubris, though, so much as fanaticism, in this case secular and vengeful.

This is a jesuitical whitewash job of the Jesuits panoply of factual and heinous high

crimes against Portugal and its king. Pombal was an extremely rare and astute national hero who for a time saved his nation from their despotic, ruthless control of the diabolical SoJ. For the real facts, consult Theodore Greisinger’s History of the Jesuits, or Edmund Paris’s History of the Jesuits, or similarly suppressed tomes of historical fact.

This is a jesuitical whitewash job of the historical heinous crimes of the Jesuits upon Portugal and the astounding heroism of Pombal in ridding his nation of the diabolical menace of the SoJ. For the real facts, and not just the Roman Catholic sanitized version which Curtius is presenting, consult the suppressed historical tomes HISTORY OF THE JESUITS by Karl Greisinger and SECRET HISTORY OF THE JESUITS by Edmond Paris.

Note: i think my last comment was censored out the last time i tried to post it. Please tell me that ROK does not engage in such SJW tactics,

If Voltaire condemns your anticlerical policy, that’s a pretty good indication of it having gone too far.