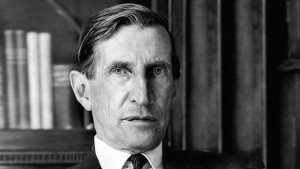

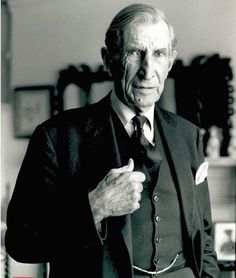

On August 3, 2003, an old man of ninety-three died quietly in a rest home in England, leaving behind him a sixty-year legacy of travel experiences, a series of elegant books, and an incredible archive of photographs taken by him throughout the Middle East and Africa. His name was Wilfred Thesiger, and he was one of the most colorful and intrepid British explorers of the twentieth century.

He traveled extensively with, and lived among, the native peoples of the Sudan, Saudi Arabia, southern Iraq, and Kenya, enduring extreme hardships under the most arduous conditions. His only peers in Arabian exploration are Richard Burton and Johann Burkhardt, who belonged to the previous century.

Thesiger was born in what is now Ethiopia, the son of a career British diplomat. His experiences and memories there, he tells us, “implanted in me a lifelong craving for barbaric spendor, for savagery and colour and the throb of drum, and it gave me a lasting veneration for long-established custom and ritual…” His education was furthered at Eton and Oxford, though without the barbaric splendor. He did, however, excel in boxing and other vigorous sports, and displayed an affinity for languages.

During the 1930s, he participated in African expeditions in the Sudan and Abyssinia under the auspices of the Royal Geographic Society and the Sudan Political Service. These early experiences honed his proficiency in Arabic and Islamic customs, knowledge that would prove invaluable to him soon enough.

When war came in 1939, Thesiger was attached to a British auxiliary unit in the Sudan that conducted hit-and-run raids into Italian Abyssinia; he was decorated for his involvement in an attack on one garrison at Agibar.

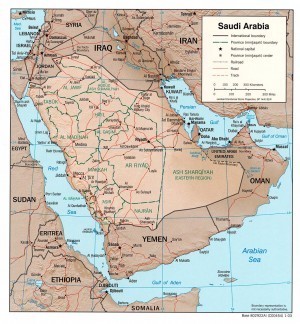

The winding down of the war, and the British Empire, placed Thesiger finally in a position to execute a plan he had contemplated for years: to explore the remote, nearly unknown desert interior of Arabia. Even well into the twentieth century, the wastes of southern Arabia were known only to the few hardy Bedouin tribes who haunted them; and they, existing in a perpetual state of warfare with each other, revealed nothing to the despised عجمي (ajami), the “foreigner.” Even other Arabs knew well enough to give them a wide berth.

Not even the Romans had been able to subdue the peoples of this area. According to the Greek geographer Strabo, a Roman expeditionary force commanded by Aelius Gallus was sent to win over the region for the empire in 26 B.C. It was destroyed by disease and native treachery in the Arabian interior, after having been deceived by local guides.

Southern Arabia retained its independence, and no foreign power–neither the medieval Arabic caliphates nor the Ottomans–ever entirely controlled them. The situation had changed little in the intervening two thousand years. As Thesiger relates in his classic account of his travels, Arabian Sands (1959):

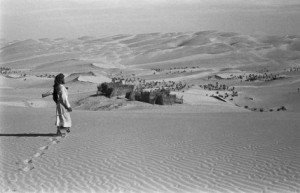

The southern desert [of Arabia] stretches for nine hundred miles from the frontier of the Yemen to the foothills of Oman, and for five hundred miles from the southern coast of Arabia to the Persian Gulf and the borders of the Najd. The greater part of it is a wilderness of sand; it is a desert within a desert, so enormous and so desolate that even Arabs call it the Rub al Khali, or the Empty Quarter.

It was into this cauldron of sand, heat, flies, and tribal conflict that Thesiger now plunged. Already proficient in Arabic, he prepared extensively by educating himself in Islamic rituals and customs, from the tiniest details of ablution to the most intricate and recondite aspects of Bedouin toiletry.

He would go barefoot, as the natives did, for Thesiger made it a point of pride to subject himself to as much brutal discomfort as possible. In this habit he was similar to his progenitors of Arabian exploration, Johann Burkhardt and Richard Burton. This passage in Arabian Sands gives a revealing view into the author’s thinking:

Soon after dinner I would spread out my rug and sheepskin and, putting my dagger and cartridge belt under the saddle-bags which I used as a pillow, lie down beneath three blankets with my rifle beside me. While I was among the Arabs I was anxious to behave as they did, so that they would accept me to some extent as one of themselves. I had therefore to sit as they did, and I found this very trying, for my muscles were not accustomed to this position…For the same reason I went barefoot as they did, and at first this was torture. Eventually the soles of my feet became hardened, but even after five years they were soft compared with theirs.

Thesiger’s pretext to conduct explorations was his hiring by a British firm searching for locust breeding grounds in southern Arabia; but he appears to have financed a good deal of his travels himself. He had no family and would remain a bachelor until his death at the age of ninety-three; for such men, travel is the all-consuming passion of their lives.

In 1946, he crossed into Arabia from Oman with a small party of Bedouin. Some of his party refused to continue, but he pressed ahead with several youths from the Rashid and Bait Kathir clans, whom he had won over with his humility and willing austerities. A second journey into the Empty Quarter was undertaken in 1947 from Yemen.

This time Thesiger was not so lucky; ignoring royal directives from the Saudi king to proceed no further, he was arrested and jailed in Sulayil. His charm quickly secured him release, and he eventually made his way to Abu Dhabi, which in those days was little more than a provincial backwater.

The details of these travels were collected into what would become one of the great travel accounts of the twentieth century: Arabian Sands. Published in 1959, it was written by Thesiger during an intense period of seclusion in Copenhagen, which he found to be a necessary aid to concentration. The book has a vigorous and unadorned prose style, and is illustrated with photographs taken by Thesiger himself. It remains a classic of its genre.

Thesiger was an outspoken opponent of petroleum exploration in the region, rightly believing that its attendant riches would corrupt both holder and recipient. An ardent traditionalist and romantic, he was a nineteenth century figure profoundly out of place in the postwar twentieth century world.

The remainder of his life would be occupied by travel and writing. He lived for a number of years among the so-called “marsh Arabs” (the Madan) of southern Iraq in the late 1950s, gaining their trust and learning their ways. These experiences were recounted in The Marsh Arabs (1964), a precious travel record in its own right.

Further travels followed to other regions of Africa and the Middle East, too numerous to mention here. He was knighted in 1995, and surprised himself by living into the new century. His extensive collection of photographs, numbering over twenty three thousand, show a remarkable eye for artistic composition and attention to detail. They are housed in a special gallery at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

Thesiger was perhaps the last of the great British Middle Eastern explorers in the traditional mold. His place in the history of travel is assured, although we cannot quite rank him with Burton or Johann Burkhardt. Thesiger never traveled in disguise, like his predecessors, and never presented himself to be anything else than what he was.

Burton, however, was a far better linguist and ethnographer, and took greater risks; and Burkhardt was the original pioneer who blazed the way for both of them.

Yet Thesiger was perhaps the more accessibly human of the two; he is frank, self-effacing, and not without a wicked sense of humor. He is a gentleman, with a nobility of spirit that shines through in his obvious affection for the local peoples to whom he never condescends.

In him we feel the pulse of a man compelled to test himself relentlessly against the extremities of travail, to push the boundaries of his zone of comfort, and to seek the churning unknown inside himself. By navigating the wilds of the desert, with its desiccated features and ghastly expanses, he sought and found his own soul.

Read More: Into The Wild

Wow, to have traversed The Empty Quarter, home of many myths, legends, and occult occurences since the dawn of man!

“a British firm searching for locust breeding grounds in southern Arabia”

I don’t quite get why anyone would search for locust breeding grounds.

I wonder if he listened to Over the Hills and Far Away at some point while he was there. I always found that tune one filled with the spirit on display here.

I think the idea is that if you know where pests originate from, you can more easily control them. The same idea is used in control of mosquitos and rats.

Never married no family and travelled a lot.

It can certainly be said he “went his own way”.

an original MGTOW…

Why humanity needs to get its’ ass up into space cause there are no more “empty quarters” in the world now. We need new frontiers….

And is the world richer or poorer for that?

i believe a world in which extremists – explorers, anarchists, inventors, etc. – is a richer place. While not practical or even desirable for most people, those with a single minded pursuit serve as ideal and a yardstick for our own thoughts and actions.

So what happens when our best don’t leave any progeny? Especially considering a man can easily have children when he is older, after his most productive years are over?

Are they the best, though? That’s a qualifier I did not use. Let’s face it, many of these people who do such extreme pursuits are fucking strange cats. Personally, I think the Renaissance man approach leads to the “best” man, but I’m also pretty sure that is just personal confirmation bias.

How do we know there are no versions of him running about with Bedouin names?

He might have left certain things out of his journals. Maybe not a kiss and tell sort of guy.

Sad when the best don’t have children. You can hope that nature throws out someone elite by sheer weight of numbers but it is still unlikely to produce the raw achievements of when eh genetic best are conditioned to breed with one another. Look at the olympics. Some island nations of no more than 80 thousand e.g Grenada achieve much greater feats than say India of some 1.1 billion. This is not blind luck.Same way the Ashkenazi being 0.2% of the total world population can achieve 65% of major academic awards.

Then maybe the population craps itself out and gets down to a cool billion and the world stops resembling a clogged sewer system.

The progeny of greats is often extremely disappointing anyway so we don’t need Michael Jordan banging Amal Amaluddin (sp) just to breed people who wilt under the pressure of greatness most of the time anyway.

Most of the best men in history, not all but most, came from adversity or from un-great parents and left the earth with no issue OR with inconsequential weaklings. Obvious exceptions of course sprinkled throughout history, but there’s no getting around the fact that Edward I, a great man by any measure, left behind a weak homosexual leaning twit, or that we have yet to feel any impact from the spawn of men who reproduced such as Thomas Jefferson or Washington or Andrew Carnegie.

The people who chooses who gets a noble prize are Ashkenazi, so of course they will give their tribe more prizes. Obama even got one for doing nothing.

The difference between him and the modern mgtow’s is how he pursued adventure and exploration. The average millennial ‘man’ that ‘goes his own way’ spends his time bitching about women on Internet forums instead of carving out a genuine path for themselves like the gentlemen mentioned above.

Yeah that’s a big problem.

This is why I advocate finding a “vocation”. It matters not what it is either.

Let’s use Thesiger as an example. Anybody in our post modern times might be able to dismiss him and say “big deal. He travelled a lot, allowed himself to have a hard time, and took as many pictures as just about any woman on facebook” (leave out that Thesigers pictures were more useful).

But in his case what he has was a vocation, a study of it, and went where few people wanted to go and went native too.

He did not change or improve the world, but that’s not the point either. I think very often, and in particular with millenials and much of what’s left of Gen X that’s not waddling around in a Prozac and blood-thinner fog, fall into this idea that if you go your own way but are told that you should not waste their lives, it meaning trying to become the next Einstein, Tesla, or Pasteur. But seeing that they are not these men and would have a long way to go before even getting close to that greatness, they give up and just spend their time eschewing women and making a job of that and finding more neckbearded ways of living.

We should consider the “greats” in poetry and literature who did not become so until they were dead.

So what does it matter, except to you?

And I can say firsthand that having a vocation, a specialty, a pursuit, is KEY to any kind of MGTOW direction. It does not mean you get to sit on your ass, nor does it mean you have to work yourself to death. It means what you want it to mean. Hence the “own way” thing – nobody else gets to decide, determine, trademark, monetize, and finally, control you.

And it need not even matter to anybody else. That’s the problem: everybody wants to be the special snowflake who changes the world. That’s SJW speak. Look at how they “change the world”. They are bringing it back to the 1930s and don’t even see that, blinded by their own “greatness” but look how much it matters to them. We’ll be stepping over piles of their bones and they’ll be the ones who went out happy.

So if the modern MGTOW is to be called out on anything, it’s the failure to think “Now what?”. Because once you have gone your own way, you still have to go somewhere.

make 99$ hourly@40:

you

Can Find Out HERE,,

✺✺✺✺✺✺ >>::http:.//CareersFullProviders..com…<<<

✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺✺

I like where you’rE going with this…

Well said.

So weird how my reading always syncs up with the articles here. I just read his book The Marsh Arabs last week. Thesiger is a hero. He always won the respect of people who lived incredibly harsh lives by adapting to their lifestyles. There aren’t many men who could do what he did.

Another English traveler/adventurer to check out is Patrick Leigh Fermor, who walked across all of Europe on the eve of WWII and wrote about it in a trilogy of books.

http://www.amazon.com/Time-Gifts-Constantinople-Holland-Classics/dp/1590171659

Good on you to reference Patrick Leigh Fermor. He is the originator of the “travel memoir”. He walked across Europe a bunch of times. He did this “monestary ” tour and stayed in Benedictine and Trappist monestaries across Europe. Best insight into monastic life I’ve read….

Glad to hear that. The British seem to breed such men in abundance, then set them loose on the world.

Well, they (we) used to anyway. Not to worry though, their (our) great Anglo Saxon lineage, customs, traditions and culture are being erased by the powers that be. Always was so bothersome, all of that energy and enthusiasm and thirst to explore and discover.

Never heard of him before. Thanks! I’m heading to the (out of print) bookstore today to see what I can find written by him.

The drive and dedication to a singular purpose like that is highly admirable. A trait of a true man, to be certain. Never heard of him until now, but feel rather inspired to pick up his book.

Keep in mind that, like Lawrence, Thesiger had homosexual leanings. Explains a fair bit about singularity of purpose.

Interesting. If so, at least he kept them in check and found something useful to do with his life. Better than what goes on today with “in your face” 24/7 Gay Pride.

We don’t know that for certain…he was a product of the old-school British school system, in which men and women were segregated. He definitely preferred the company of men, but I don’t think we can say much more than that. Or at least his biographer is silent on it.

Good point. Men generally used to prefer the company of men, which is lost on younger men because they’ve been raised in a culture which instructs them that any contact with men outside of work and an occasional sanctioned once a year “guys night out” hints at “gay”. Even normal friendships are labeled “bromances” now in order to convey a subtext of homosexuality to them.

Didn’t used to be like this. My grandfather, an extremely masculine man who even now could rise from the grave and kick everybody on this site’s arse while smiling, generally spent his free time away from the house with other men doing man things. When he was at home he was working on restoring cars (his hobby) and other men would wander over and shoot the shit, share a beer and lend a hand. Grandma’s place was *not* hovering around him. He loved her dearly, but if she’d hung around or expected him to be around her 24/7 he would have patted her on the head and told her to go fetch him a beer.

Today though? Modern culture tells us that something “is not quite right” about this. Fucking bullshit.

Seems to be quite common in the British.

Probably why they liked the middle east so much.

A great look into the life of another 20th century renaissance man. Thanks Quintus.

“It was into this cauldron of sand, heat, flies, and tribal conflict that Thesiger now plunged. Already proficient in Arabic, he prepared extensively by educating himself in Islamic rituals and customs, from the tiniest details of ablution to the most intricate and recondite aspects of Bedouin toiletry.”

That has to be a nudge nudge wink wink allusion to the central anthropological fact of Arabian custom: how exactly did Thesiger ‘prepare extensively’ to get shat upon by lusty Saudi men?

And if this cauldron of sand becomes the nucleus of any extended caliphate is this the fate we will all ultimately suffer.

Forget beheading videos

Now, now, Michael. Be nice.

My apologies. I meant to post this on the other ethnography article. Actually I did a course on ethnography once – one starts as an outsider looking in, but in order to fully live and embrace the culture of interest one seeks the privileged insider position, running all the risks of going native and losing ones perspective, losing ones capacity for iterative self reflection and the possibility of reporting upon what one has experienced in the sacred encounter with the (in this case oriental) Other. Just like with those Instagram girls really. A lot of the course was about how the western anthropologists / ethnographers exploited the ‘native’ peoples.

Bedouin tribes were of no account. They wandered the sands from the Mediterranean coast to the Persian Gulf and the discovery of oil in those lands and the placement of Israel only influenced by whom they would be dominated. No one wants them, their offshoots are Palestinians and serfs in Kuwait, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Little to be learned from this article. Just because Thesiger actually communed with these “people” doesn’t make it a worthy exercise.

The man wasted that part of his life. Better he shape the relevant world than report of ignorant Bedouin. Fact is, the Bedouin wanted no part of the industrialized world, it would have meant work. Civilized society wasn’t afraid of them, they merely had no use for them, they were content to allow them to move along.

I don’t agree with your statement. Ethnographers, linguists, and anthropologists all recognize the value in exploring and documenting aboriginal customs. The regions Thesiger explored were some of the oldest cultures on earth, and for that reason alone, their study is worthwhile. If they have survived for thousands of years, they must be doing something right. They outlasted the Romans, the Ottomans, and the British, and they will outlast us.

Besides this point, it is the journey itself that has value. Explorers do it for the challenge, the adventure, and to feel the joy of being alive.

Far better to die of dysentery, thirst, or a bullet in the Arabian sands, than to slowly become zombified working as a menial clerk in some megacity.

The choice is yours.

Bit of a mixed reaction. i think there is a worth in learning customs of some groups but western anthropologists play these customs as having some secret sub-context that i shall never be privy too with my white maleness. that is pure arrogance on their part and one i shall not pander too. I wandered through bedouin tribal lands in north africa through morocco and onto algeria and through bedouin lands in Jordan, Syria , Israel and what would be called Palestine. it all varies with how you deal with these people. In north africa they are far more trusting and accommodating than their arab counterparts who they have a troubled relationship with at best. They are lazy in a working sense in the same way that most tribal societies are work-shy and the arabs play that card to their advantage in north africa. In israel and levant they are troublesome for both the arab jordanians and syrians they are nomads and stress the system of their host country.i recall when people say that aboriginal australians were untouched for 40,000 and now live in tin huts. the same can be said of the bedouin. outside of some enclaves in north africa they live no better than a bushman’s dog.a life certainly not fit for envy.

And the Frisians are a small minority group of people who are neither Dutch nor German nor English. Yet we value studying their language and culture since it was from them that the Anglo Saxon languages and customs formed, which in turn created the group of people who today have maximum influence over the world.

The study of human cultures, traditions and linguistics is always a good endeavor, even regarding minor or failed societies and people, if to only instruct us what *not* to do.

You criticize him, who spent blood, sweat and tears, who documented and published well received tomes in his day. That leads me to ask how you’ve chosen to not ‘waste your time’ on this globe.

“..Fact is, the Bedouin wanted no part of the industrialized world…”

How strange!

What exactly was their beef with pollution, manginas, hell-whores, faggotry and slave-labouring at the factories ?

Pray tell !

Saudi Arabia really is a beautiful country. I lived in Tabuk for four years in the mid 90’s and ventured on camping trips out to the Red Sea and into the desert with it’s never ending mountainous sand dunes. With that said, it can be a very dangerous place for foreigners which makes Thesiger’s story that much more incredible.

(Picture: view of our campsite from the top of a dune)

Very bleak and beautiful. Deserts have always given me the heebie jeebies though, could not imagine living in them. Mountains on the other hand, could wander for the rest of my life lost in the Rockies or in the Alps.

Where do I sign up for your book club? My reading list grows whenever you post Quintus.

I’ll try to keep you productively occupied, Bear Hands….

I wish I would have read something like this prior to college as I think my life would have taken a different arc. At the very least, I take inspiration from Thesiger’s willingness to subject himself to the greatest hardship.

I read a few of his books years ago. He is a very good writer.