An expert in classical Chinese once wrote that ancient texts occasionally feature characters that appear once, and only once, in the existing literature. The linguistic term for such words or characters is hapax legomenon. Because of this uniqueness, we are told, it is not possible to know precisely the meaning of a hapax character. A scholar, for example, might be confronted by a sentence that reads, “The chariot moved across the battlefield with the furious speed of an X.” One translator, using his best informed guess, might render X as meaning such-and-such; and another translator might render X as something else. But the truth is that we can never know precisely what the meaning of the character X is. It is unique. As a hapax legomenon, it will remain forever cloaked in mystery.

Men can also be hapax figures. They disturb the convenience of our lazy taxonomies by refusing to be pidgeon-holed as one thing or another. Such men defy easy categorization; they can never precisely be pinned down to our butterfly-board. Just such a character brimming with contradictions was German writer Ernst Jünger. Impassioned warrior, biologist, writer, philosopher, mystic, nationalist, and believer in psychedelic drugs, Jünger stands alone among twentieth century writers, laughing at our attempts to fit him into any one box.

He was born in Heidelberg in 1895 and had a reasonably comfortable middle-class upbringing. Running away from home in 1913 to join the French Foreign Legion, he served briefly in North Africa, after which his father brought him home. Still lusting for combat, he volunteered for the Kaiser’s army in 1914 and served with great distinction on the western front as an infantry officer and storm trooper. He received the Iron Cross First Class in 1917, and finally Imperial Germany’s highest military decoration, the fabled “Blue Max” (the Pour le Merite) at the age of 23 in 1918. Wounded many times during night patrols and trench raids, Jünger found the war to be a supremely transcendent experience, a distillation of the struggle of life, and the core of masculine identity.

Trench raider: Jünger was intimately acquainted with scenes such as this

Throughout the war, Jünger kept a private diary of his experiences, and these scattered thoughts formed the nucleus of a book which he self-published in 1920 under the title In Stahlgewittern. Appearing in English under the martial title Storm of Steel, the memoir catapulted Jünger to prominence. There is nothing like it in all war literature. It deserves close examination on our part. As a hospital orderly once told Jünger philosophically while dressing one of his wounds: habent sua fata libelli et balli (“books and bullets have their own destinies.”)

The first thing that strikes us in Storm of Steel is the tone: here there is no morose hand-wringing as one might find in the weepy writings of Erich Maria Remarque, Siegfried Sassoon, or Robert Graves; none of the clinical detachment of Adolf Von Schell’s dry and lifeless Battle Leadership; and none of the pacifist sniveling that mars some of the work of Ernest Hemingway. Instead, we are thrown right into the thick of the action, swept up with Jünger in the exhilaration of proximity to instant death, as bombs burst all around us and a determined enemy is waiting beyond the lip of our trench to cut our throats.

Jünger with the coveted “Blue Max” decoration, which he received in 1918

The Greek philosopher Heracleitus believed that Fire was the essential force that moved the world; and under the spell of Jünger’s prose, we actually come to believe this to be so. We are stupefied by the lyric poetry of flame, fist, and iron, as the earth trembles beneath our feet during artillery bombardments; and we huddle with Jünger in soggy, putrid shell holes, waiting for the opportunity to plunge a dagger into a British Tommy’s gut. Jünger takes it all in with the wry humor and determination of a true combat soldier, never boring us with mealy-mouthed questions about the war’s origins and purpose; for him, the war is a mystical experience, bringing an elevated awareness of the agonies and joys of life. Combat and pain are the quintessence of life. There is only survival in the present moment, and the supreme experience of hunting down and killing the enemy. Among countless memorable passages, the following will give a flavor of the whole:

The trench was appalling, choked with seriously wounded and dying men. A figure stripped to the waist, with ripped-open back, leaned against the parapet. Another, with a triangular flap hanging off the back of his skull, emitted short, high-pitched screams. This was the home of the great god Pain, and for the first time I looked through a devilish chink into the depths of his realm. And the fresh shells came down all the time.

Jünger’s prose approaches the beauty of Virgilian hexameters with this sentence, describing the German response to an attack by French aircraft:

The anti-aircraft guns threaded long fleecy lines through the air, and whistling splinters pinged into the tilth.

About the thrill of marauding by night into enemy lines, Jünger has this to say:

These moments of nocturnal prowling leave an indelible impression. Eyes and ears are tensed to the maximum, the rustling approach of strange feet in the tall grass is an unutterably menacing thing. Your breath comes in shallow bursts; you have to force yourself to stifle any panting or wheezing. There is a little mechanical click as the safety-catch of your pistol is taken off; the sound cuts straight through your nerves. Your teeth are grinding on the fuse-pin of the hand-grenade. The encounter will be short and murderous. You tremble with two contradictory impulses: the heightened awareness of the huntsman, and the terror of the quarry. You are a world to yourself, saturated with the appalling aura of the savage landscape.

Describing the ghastly contradictions of combat, he notes ironically:

We started to dig trenches right across the village, and erected new walls near the most dangerous places. In the neglected gardens, the berries were ripe, and tasted all the sweeter because of the bullets flying around us as we ate them.

And here, Jünger dispatches an enemy soldier with emotionless precision:

I spotted a British soldier breaking cover behind the third enemy line, the khaki uniform clearly visible against the sky. I grabbed the nearest sentry’s rifle, set the sights to six hundred, aimed quickly, just in front of the man’s head, and fired. He took another three steps, then collapsed onto his back, as though his legs had been taken away from him, flapped his arms once or twice, and then rolled into a shell-crater, where though the binoculars we could see his brown sleeves shining for a long time yet.

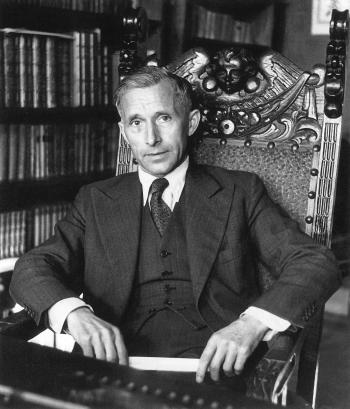

Jünger in his later years: despite the suit, every inch a fighter

After the war, Jünger remade himself as a biologist and entomologist, although insects were never quite as appealing as combat. By his own admission, he “hated democracy” and parliamentarianism, and was a conservative nationalist; yet to his credit, he also despised fascism and National Socialism. He refused a seat in Hitler’s Reichstag in 1933, forbade his writings to appear in Nazi publications, and was careful to distance himself from any endorsement of Hitler. He was mobilized for military service in the Second World War, but spent the war years mostly in occupation duty in Paris.

Jünger remained a committed individualist, never wanting to be beholden to anyone. After 1945, he was briefly banned from publishing for his refusal to kow-tow to the Allied occupation authorities. He continued to write, however, eventually turning out more than fifty titles. In the postwar years, his uniqueness shone forth in all its intensity. In his treatise On Pain, he argued that the experience of pain, and man’s capacity to deal with it, was the central question of the human condition in the modern era. More bizarre was his enthusiasm for hallucinatory drugs: his later writings (e.g., Approaches, appearing in 1970) chronicle his dalliances with cocaine, hashish, and LSD. He was also an adherent of the “magical realism” movement, a literary school which held that magical or fantastic qualities permeate the experience of ordinary life. We cannot be sure he was wrong.

Actually, Jünger led a charmed life, outlasting nearly everyone. Gradually his literary star rose to prominence; by the 1960s and 1970s, he was one of Germany’s most respected writers. In 1984, he, along with the presidents of France and Germany, dedicated a battlefield memorial at Verdun and publicly condemned militarism. Yet he never regretted or apologized for anything he ever wrote, proudly proclaiming his belief in the power of the individual over that of the mechanized state. He died in 1998 at the age of 102.

German Idealism, which had begun with Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel, had seemed almost a spent force until the advent of Ernst Jünger’s Storm of Steel. In many ways, he was the final, explosive culmination of the stubborn Idealist strain in German thought, a thread that thankfully has not quite yet died out. But Jünger is stranger still; his body of work synthesizes so many disparate strands that he really is in a class by himself.

As a lyric poet of total war, and as an apostle of the cathartic power of combat, he remains unsurpassed. He is a Teutonic hapax legomenon, a character standing alone, whose true meaning we can only guess at.

Read More: The Renaissance Of Modern Man

Thanks for this. Jünger was a titan. One of my favorite passages is from his book, ‘On The Marble Cliffs’ (1939):

“That I was certain of something which I had often doubted–there were still noble beings amongst us in whose hearts lived unshakeable knowledge of a lofty ordered life. And since a high example leads us in its train, I took an oath before this head that from that day forth I would rather fall with the free man than go in triumph among the slaves.”

Instead of worshipping multi-cultural pussies, fuckheads, flamers, and wusses, young Germans need to be celebrating this guy. Compare him to the degenerate specimens of humanity that you see in Western Europe now.

Agreed. One only need look at the ode to degeneracy that was the Berlin love parade to see how far they have fallen. Boy, was I in for a load of disappointment on my first extended stay in that city. To be honest, I still don’t know to this day why exactly it is so hyped and raved about around the world. Asides from the more notable landmarks and museums, what else have you got? Cheap accommodations and eateries, trashy clubs, and post-DDR “charm”? And I came in with a VERY open-minded and positive attitude to boot, only to leave with an unshakeable feeling of “meh” towards the end.

You got many nicer and more picturesque places in Deutschland to visit, though they are also usually quite a bit “cleaner” as well. Makes you think now, don’t it?

Hmmm…were you in Munich? I’d like to go to the Oktoberfest there one day.

Yeah. It’s a very nice city with a decent center and a neat multi-lane bike highway circling around it. The people are also usually much more stylish and statuesque than in other German cities in case that matters to you. Overall a good experience, though it can be expensive. In general, the south east of Germany is noticeably nicer than the north IMHO.

It too (the current degeneracy an decay) shall pass. The Weimar years were unsurpassed in degeneracy, depravity of every kind.

Society moves in cycles hopefully. A look at the history of the “Twelve Caesars” by Suetonius can give you an idea about it. Especially the chapters about (Octavian Augustus). When all was loose, the Roman empire was in a free fall, decaying and depravity was becoming rampant (nude festivals, homosexuality, lack of decency from the artists and the “populace” etc.), needed a strong leader like him and Iron fist to put an end to it.

I guess we will soon see the rise of “Crisis Leaders” soon enough and after a bloody mess, things will once again go back to their place and all will be happy and prosperous, for a little while of course.

I’m totally speculating here but I get the impression that Germans these days are afraid to take too much pride in themselves for fear of being decried as modern day Nazis … in this way, it kind of makes sense to me that they would elect someone who looks like a dumpy hausfrau as their leader …

Your speculation is correct. Almost all expression of patriotism is taboo in Germany.

Indeed. All across that land they could seriously benefit from somebody ready to vigorously whip them back into shape. Maybe a leader of some sor… woo, easy there. Best not give them any ideas they might like and implement.

The Japs are trying to reverse that though

Yes, I wouldn’t write the Japanese off yet. They have tough times ahead with the looming demographic crisis, but they have a good chance of making it through. I wish America had Japan’s problems. Our are 100 times worse.

Truth is that Japan has been over-crowded for some time, so a declining population isn’t bad. The good news is that they aren’t flooding their country with non-Japanese at the same time. In the US, Americans have Japanese style birth rates combined with a suicidal immigration policy. Whatever the US is in the future, you can guarantee that it won’t be American. It will be a mish-mash of inferior third-world peasant stock.

Lucky for Japan that China is pushing around all of its neighbours in the south sea, pushing them into alliances with Japan.

I think Japan may re-militarize to counter the growing threat from China. Their current Prime Minister is fairly nationalistic and increasing military spending and trying to resurrect Japan’s military mojo.

There is a stark difference between not taking pride in oneself and adopting some sort of generalized collective pathological depression along the way. Looks like losing the war and the subsequent cultural “reeducation” courtesy of the victorious powers really did a number on those people.

A truly brilliant article on a great individualist writer. Currently living in Germany myself, I have to say that its strong, noble sense of idealism mentioned in the article has withered and waned. Young Germans have unfortunately given into American idols and lost the unique, burning fire that Germans especially are renowned for possessing. (Having said that, Germany is far better than others in this regard) I particularly enjoyed Junger’s novel “The Glass Bees” which shows how a more traditional, idyllic upbringing, (be it full of physical and mental pain) has been sacrificed for a mechanized and artificial modern culture. Having said that, I do remain optimistic that an individualistic, passionate lifestyle can still be pursued, just as Richard manages to do at the end of Glass Bees.

Thanks for your comment, Rodion.

I have to admit that, to me as a non-German, Junger is the quintessence of the German spirit.

I wanted to leap into the trenches with him and fling a grenade at the British.

But he was also a learned man and an expansive thinker.

I hope the Germans get their act together and stop buying into American bullshit.

Couldn’t have put it better myself. At least we are having the conversation now and thats the first step to changing things.

Not so poetic, but I catch your drift…

War is the most important human experience. All other values rest upon strength.

Junger commited the sin so many of that generation did. He fought for the wrong side. He made Europe and Germany safe for the foreigners. He sinned against his race and his people. He should have been a great friend to the National Socialists.

A great warrior…who fought for the wrong people. Good, but not good enough to idolize. He needed permission and the uniform to hide behind.

This is Junger, early 1940s.

[IMG]http://i.imgur.com/H5ignCI.jpg[/IMG]

You can say anything you like about the Nazis but not that they had a bad taste. Hugo Boss designed their uniforms.

One of my drill sergeants during basic posited that generally speaking it’s the nation with the ugliest uniforms that wins the wars. It’s an interesting theory. If it’s true then we’re truly fucked if we get into war with China, they look positively shabby.

That’s known as the “Sukhomlinov Effect”. Named after General Valdimir Sukhomlinov the Russian minister of war during WWI. Here http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sukhomlinov-effect.htm

He was not on the wrong side in World War I. What other side would he take after all, it was a nationalistic war, not so much an ideological one?

sorry, what on earth are you on about? How is it that Juenger fought for the wrong people. He fought for germany in both world wars. He was a memebr of the Freikorps in early 20s.

“the experience of pain, and man’s capacity to deal with it, was the central question of the human condition in the modern era.”

Truth right there. 100%

Superb article. Quintus is and has always been one of my favorite authors, as there is always so much wisdom to learn from his posts. Great post.

Ah, a friend recommended this book, and I can see why. Seems he blends a poetry in his writings that doesn’t detract at all from reality.

While not quite a literary masterpiece, I derived much wisdom from Marcus Luttrell’s Lone Survivor, and have begun to read Service, which seems off to an equally good start.

“As the storm raged around us, I walked up and down my sector. The men had fixed bayonets. They stood stony and motionless, rifle in hand, on the front edge of the dip, gazing into the field. Now and then, by the light of a flare, l saw steel helmet by steel helmet, blade by glinting blade, and I was overcome by a feeling of invulnerability. We might be crushed, but surely we could not be conquered.”

Best Quote of the Book

Brave and tough he might have been, yes, but he fought in stupid wars.

I don’t think Option C – Sit It Out – was available in Germany, or most nations, at the time.

Nor option D – shoot the real bastards responsible for creating these crimes against humanity in the first place.

Aye, I know. Plus there was too much honor and integrity for most to subscribe to assassination politics. Hell the entirety of WWI was because of a nutball assassin and the world’s reaction to his acts, at least at a superficial level.

Superb writing of a complex man. Perhaps his writings could be included in a Selective Service packet which presently, and hypocritically, is only required of 18 year old men in the U.S. to file. Nothing like coming to terms with reality to open the doors of perception.

As Tolstoy described the Russian soul, Junger describes the heart of Germany. A man amongst men.

A note on Chinese characters: because they are pictographs composed of different radicals, which are less complicated characters fused together to make a different one, the meaning is bit easier to determine, unlike in a Roman style alphabet. If one can identify the radicals, one can decipher the meaning with relative ease. Literal chinese is itself a deep language very philosophical in the way it creates compounds, it’s a very fascinating system. One can see why the Chinese have a highly developed philosophical outlook. There is a reason they were using texts like Romance of the Three Kingdoms as exam material for civil service for hundreds of years.

I think you’re being a little unfair to Sassoon, as well. He was a man of deep conviction obviously, and it took a lot of stones to challenge the British status quo at the time, and did so alone, in which every military problem had one solution: more meat in the grinder. Also, after all of it, he wanted to go back in the trenches. He knew it was bullshit but wanted to go back anyway. Weepy? Dude, single handed, captured an enemy trench, with a handful of grenades, and then sat down to read a book on poems he brought with him, alone in enemy territory. He was recommended for a VC (never got it though). Anyway, his Sherston trilogy is excellent.

No disrespect intended to Sassoon. You’re right; he was a true snake-eater. I guess I wanted to draw a contrast between the writing styles of the two men.

It’s Hemingway that I have bit of hostility towards…I don’t know what it is, but he needed a proper hiding with a blackjack.

I do like Hemingway, his stripped down style at least. His service on the Italian army or his adventuring in civil war eta Spain you take issue with? I never really considered it.

Have you read any of the wwII vet-writers? Mailer’s Naked and the Dead, or James Jones’ trilogy? There’s also a great account from an Alsatian, Serge Sayer, about his time on the Russian front after being drafted into the wehrmacht, but can’t think of the title right now

I made a mistake the name is Guy Sajer the book is forgotten soldier

Hemingway, though I enjoy his writing, was self-obsessed in an almost effeminate way. “The Sun Also Rises” is as beta as it gets.

His oneitis for Brett? but the character did get his nuts shot off, or his dick, he never quite says, this gotta change a man’s outlook.

Yes.

Thanks, I had forgotten that, been awhile since I read. That said, the self obsession and need for female validation is a consistent thread in his novels. His longing for Brett, a social climbing whore, makes me cringe every time I read the novel. The petty jealous is also a bit effeminate.

Interesting. I look forward to reading some of Junger’s works. Thanks for the heads up on this.

“By his own admission, he “hated democracy” and parliamentarianism, and was a conservative nationalist; yet to his credit, he also despised fascism and National Socialism.”

I imagine that describes more than a few ROK readers as well, myself included.

You’d think the nature of trench warfare would make it difficult for infantrymen to distinguish themselves. Rake the enemy’s lines with artillery, go over the top, run like hell, and pray that their machine guns had been silenced. On the other hand, by definition you’d have to be a stone cold badass to sprint across No Man’s Land.

Junger was one such badass as Quintus has shown. On the American side we had Alvin York. Dude won the Medal of Honor for single handedly taking out a German machine gun nest. After firing every rifle round he had – one shot, one kill – the Germans rushed him with a bayonet charge. He drew his .45 pistol and shot them all down before they could reach him. Later in life he thought we shouldn’t have gotten involved in WWI, but come Pearl Harbor he tried to reenlist at the age of 54. The Army wouldn’t put him in combat, but commissioned him in the Signal Corps.

Kudos to Quintus for bringing Jünger before RoK readers. One of my favorite quotations is to be found on Jünger’s Auf den Marmorklippen (On the Marble Cliffs): “Tief ist der Haß, der in den niederen Hertzen dem Schönen gegenuber brennt.” (“Deep is the hatred that burns in base hearts in the presence of beauty.”)

Excellent article Quintus. I would like to see an article from you about Francis Parker Yockey and his book Imperium.

Reading about brave European men like this makes me wonder how we got to the emasculated men we have today

It happened little by little. The scum, degenerates, and feminists slowly chipped away at the edifice. And the leadership element, instead of crushing it with a brutal fist as they should have, molly-coddled it.

They snuggled up the scum in order to get laid, to make money, and to gain fame. In short, they proved to be spineless vermin, unworthy of life.

They hate masculinity because it represents everything they are not. As commenter Borges de Oliveira noted in his comment [see above], “Deep is hatred that burns in the hearts of the base when confronted by beauty”.

And this is how it started.

One can very clearly see how the flies in the market place (from Nietzsche’s So Sprach Zarathustra) have finally reached critical mass allowing them to swarm and take over, literally covering everything with their filthy little feet. Shoo vile vermin! Be gone! Must one escape into the mountains to finally escape their poisoned sting?

Cool article QC. Thank you.

The quality of the articles keep getting better and better. “Chapeau bas” Herr Quintus.

I guess its not only the Germans that lost their spirit. I noticed a common trend with the Chinese. Especially those that live outside China.

Truly pathetic is the kindest word in my vocabulary to describe this current generation.

Sometimes I wonder were that glory, that heritage of Thousands and thousands of years. Empires. Philosophies. Arts, Science and culture. Where have the examples of the sages, wise men, the greatness of emperors and ingenuity and self discipline of people gone to.

Replaced with bubble tea going, effeminate, J-Pop loving, undisciplined, skimpy shorts wearing restaurant attendants.

Their ancestors should be crying by now.

I guess its a general trend for every culture I have seen. Sad.

Hey QC any mention of Junger’s personal /romantic life in your research ?? I bet he was jodhpur deep in the frauliens and madmoiseilles ( sp?) . He’s industrial extra-strenghth red pill. I bet he blitzkrieged the bitches

Two world wars, stared death in the face countless times, lived to be 102 years old. That alone is a mind boggling thought.

Thank you, Quintus, for exposing me to many remarkable men which I didn’t know about.

Same here…I plan to look for his books now. I went through an extensive ‘psyconaut’ period in the 70’s & 80’s myself.

wow.

I have been intending to purchase this book. Now its most certain I will.

Thanks

It is a shame my formal education never exposed me to this man.

sorry, were you never told that formal education hardly ever provides beneficial stimuli?

Well, I did learn to capitalize. Does that count?

hahaha it counts for something

It’s wonderful that figures like this are being remembered and shared with the younger generation, who have been so poorly educated by schools and colleges. Junger also wrote more conventional novels, including a very cool, edgy love story set in Paris – the title eludes me but it moved me in college. Thanks for the article.

A singularly refreshing look at Jünger’s unique character, as he was and not as he is stereotypically perceived in the media. What you could have explicitly elaborated on, particularly in the context of the hapax legomenon, is his figure of the anarch from the 1978 novel, Eumeswil. Among all his exceptional contributions to the world, the figure of the anarch is perhaps the most important – a model for being free in the special case of our contemporary world. Incidentally, Jünger’s anarch was partly based on Max Stirner’s “Unique” or “Only One” (from The Ego and his Property), underlining again your very apt association of Jünger with the hapax legomenon.

For those interested, much more on Jünger on my own blog: http://www.ernst-juenger.org

Wow. Great addition to this site!

I think the point is that combat is its own realm. Peace is always preferable to war. Men shouldn’t have triangular bits of flesh hanging from their skulls. This man seems to have been someone who held this view. He engaged in combat as a way to test his mettle and preserve an equilibrium.

There was class in Prussia called the Junkers who had such a mentality. Unfortunately this more or less noble characteristic has been used to foster avoidable conflicts by powerful opportunists.

That being said I like the article and your writing in general but find a bit of adolescence in it that I think is below you.

I wouldn’t have even commented if you hadn’t said: sniveling pacifism.

The aim of a good military is as a deterrent to the wickedness of needless combat.

But you know this.